Season 01 Episode 22

Episode 22: The Immersive Producer

Roz COLEMAN - International Company Manager, Sleep No More

Original Date of Release: 18 Feb 2020.

At the time of recording, Roz Coleman was the International Company Manager of the immersive theatre experience “Sleep No More” in Shanghai. This has given Roz a unique appreciation of audience responses in different countries and cultures, and during our short chat she shares some great observations about human behavioural traits in China.

The obvious irony is that our discussion covers audience behaviour in environments where people are crammed together and inhabiting each other’s space. Well of course that’s not what we’re experiencing now in February 2020, with most facets of everyday life on lockdown in China. I hope that my chat with Roz will be a good reminder that our current situation is only temporary.

You can also listen to a catch-up with Roz at the end of the interview with Jovana ZHANG from Season 02 Episode 08.

To Join the Conversation and Follow The Graphics…

View the LinkedIn Post, the Facebook Album or the 微博 Article for this episode. Alternatively, follow Mosaic of China on WeChat.

To view the images below on a mobile device, rotate to landscape orientation to see the full image descriptions.

To Listen Here…

Click the ▷ button below:

To Listen/Subscribe Elsewhere…

1) Click the link to this episode on one of these well-known platforms:

2) Or on one of these China-based platforms:

To Read The Transcript…

[Trailer]

RC: He grinned his head off and he said “Don’t party, won't finish”!

[Intro]

OF: Welcome to Mosaic of China, a podcast about people who are making their mark in China. I'm your host Oscar Fuchs.

Today's episode is with Roz Coleman, who was the International Company Manager of the immersive theatre experience Sleep No More in Shanghai. If this phrase ‘immersive theatre’ means nothing to you, then don't worry, since we defined it with some examples very early in our conversation. And I'm using the past tense here, I was lucky to grab Roz for this interview last year before she left this role, and left Shanghai.

Being in the world of immersive theatre has given Roz a unique appreciation of audience responses in different countries and cultures, and I learned a lot from her about audience behaviour in China in this short chat. But I'll give you all a heads up, the thing I am most grateful for in this conversation is my introduction to the concept of ‘Shanghai Flow’. For anyone living not just in Shanghai, but any busy city in China, I strongly urge you to listen out for Roz’s explanation, and embrace this idea.

Let me address the elephant in the room, this is the second episode that I'm releasing during the time of the coronavirus outbreak. It's February 2020, and the obvious irony in my conversation with Roz is that we talked about immersive theatre with audiences cramming together and inhabiting each other's space. Well, of course, that's not what we're experiencing now. Shanghai street life has ground to a halt. It's now as peaceful as a small village, and everyone is keeping their distance from each other. The lane by my house now has a locked gate at the end of it, so only residents can enter and exit. My local restaurants and cafés are mostly shut, and the ones that are open have been asked by the government to only sell food for takeout. And then even going into those stores - to order food to go - usually requires the wearing of a face mask and submitting yourself to a temperature check.

As brutal as all of this sounds, I personally don't find any of these restrictions stressful, I actually find them quite comforting. And everyone's strict adherence to these tough rules only makes me feel more certain that China and the Chinese people are on top of this. To everyone listening to this in China right now, I hope you agree with those sentiments. And despite all of your current discomforts, I also hope that my chat with Roz will be a good reminder that our current situation is only temporary.

[Part 1]

OF: Well, thank you so much for coming, Roz. I'm here with Roz Coleman. And Roz, until recently, you've been the International Company Manager of ‘Sleep No More’ here in China.

RC: That's right. Thank you so much for having me.

OF: Thank you for coming. And just to explain further, you are a freelancer, but you've been working with Sleep No More for how many years now?

RC: That's right, I've been here now for a little over two and a half years.

OF: Right. And so the first question I ask is, what object have you brought in?

RC: Jingle jangle. This here is my bunch of keys. It's my bunch of keys that has, most importantly on it, my bicycle keys. And that's the key to my freedom in Shanghai, my riding around, my most favourite activity perhaps of all time in my entire life. And I have some other keys on here as well. I do, of course, have a house key, even though I'm somewhat nomadic at the moment. And I also have this key here, which feels appropriate since it was given to me by my cohorts at Sleep No More as a - almost, what can you say - retirement present, and it represents the Hotel McKinnon. And it represents, like, actually, my entire time in Shanghai here. I've always been at home making theatre in places which aren’t theatres. I've worked in the undercroft of a war memorial, and derelict office blocks, and in forests, and on beaches, and in sights of special scientific interest, in cathedrals… And I'm a member of an artistic collective called KlangHaus, which says ‘What if these walls could talk, literally?’, and makes music and light and shadow about the ghosts which inhabit our buildings.

OF: And just before you go further, can you explain what Sleep No More is, to people who don't know what it is.

RC: I would often describe it as a game of hide and seek in a haunted house, based in a hotel. But I suppose a more literal description of it would be, you show up to an elevator, you're told to leave your worldly possessions behind, you're told to follow your own path and that fortune favours the bold, and for the next few hours you will spend your time crafting your own story and landscape and narrative, as you follow extremely physical performers acting out this story amongst many thousands of other stories hidden in the walls of the hotel.

OF: That's well done, you’ve obviously done that a few times.

RC: Actually, that was the first one that kind of fell out a bit like more formed than I'd expected. I suppose I've been immersed in it for some time now. This is my first international experience, in a way, of seeing immersive received. I have done a bit in Australia when I was touring with Circa. And I have seen elements in New York, and I have got an international perspective on it. But it is so interesting to be here and see an international response. Now, when I was touring Circa, I would of course see the way in which applause differs. In France, you will do six encores, at least. And it will be an absolute tirade of standing ovations and applause. In Germany, things are taken quite seriously, but the applause will be very present and a big part of your departure from the stage. In Ireland, there’ll always be a Q&A, and you'll never be able to leave, and you'll have to escape through the back door, because everybody's talking for ages and ages and ages and simply can't stop. But China's really my first experience of seeing such a completely different international perspective. And I think, as well, because whereas in UK, Europe, New York, etc, we have this slow-burning trajectory of the history of immersive theatre - how it began, you know, we feel like we're in a theatre when we go to an immersive show, whether we're in carpark or cathedral - whereas here in Shanghai, the show has really been chair-lifted into the centre of town, with no prior examples to follow. And so it's extremely interesting as well, from that sense, to not only see an international audience response, but to see them responding to immersive theatre for the first time, with a show that is actually quite developed from that timeline, if that makes sense.

OF: Right. So what have you seen, then, the reaction being here in China, were you surprised?

RC: We have seen so many millions of little surprises that have entirely subverted any of our preconceived notions as well of how people behave in immersive theatre. Because a huge amount of your work as a producer of immersive, and as a performer, and as a director, is to somewhat second-guess your audience and say “Well, if we put them in this low-lighting experience, and we play this extremely loud noise at this point, they're more than likely to do this…”, and anticipating how you're going to take care of people. One of the things I think is absolutely primary in immersive is the way that you take care of people. And we say that we should look after every single person who comes in through those doors as if they were our 90-year-old grandmother, because this is the first time for them. And we're used to the environment, but of course everybody new coming in is not. And so we would see, for example, in New York, or in London, a phenomenon that I personally refer to as the ‘polite horseshoe’, which is a semicircle of, let's say, 10 feets’ worth of standing back away from an artistic event, in order that you a) don't crowd the performers; and that you b), crucially, do not get in the sight-lines of any of your fellow audience members. And this is a thing that has been absolutely confounded in Shanghai. It really is a moth surrounded a flame. It really is like the performers have the light, and you should be as close to the light as you possibly can without getting burned. And it's that proximity to the action that's so important. That way of paying attention, I can imagine that some of these moments have had their closest moments of attention here in Shanghai. And I've seen it again in Dragon Boat Festival a couple of years ago. I was sitting on the grass in Jing’An Park, and there was a line of drummers going up and down in a parade. And I could watch that from a distance, because that was some loud drums. But what I saw was audience standing right next to a guy with a snare drum around his neck, hammering away at it, and audience standing right right next to him and following them all the way down there, then all the way back up here, then all the way down there, then all the way back up here. And I was like “You don't need to go all the way down there. You know they’re coming all the way back up here. You can just stand there”. But I realised, that's not the point. The point is that you get in the art. And I think when we've started to inhabit this notion of how that is OK - and lovely, actually, and so passionate, and a really valid and interesting way of paying attention - the performers within the show have really got accustomed to, and very comfortable with, somebody coming right up to their face to see what's going on in the immersive environment of the show.

OF: So how did you unpick that?

RC: So I guess the first thing that I need to speak about is ‘Shanghai Flow’. This is a phenomenon that we all encounter, the first moment that we step off any elevator, any vehicle of public transport in Shanghai, and navigate one of its busy streets. And that is something that I love to see when I'm riding my bike, because it's so aware, so lacking in aggression. But it can appear aggressive, because the thing about ‘flow’ is it has to flow, it has to go in order to flow. And so when you see somebody cut in front of you on a scooter, or somebody come piling into the train carriage as you're trying to get off, that’s the thing that I would describe as 'Shanghai Flow’. And we see that in audiences around the building all the time, a way of getting front and centre first, and - even if you weren't first - feeling absolutely content to stand directly in front of the face of the person who got there before you, in order that you can see the best version of the show that you want to see. Because you're invested, and that's your purpose, and you're clear about your purpose.

OF: I've never heard of that ‘Shanghai Flow’ concept. It's obviously something which I should know about, right?

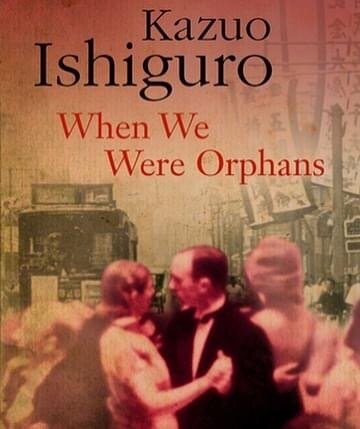

RC: It's up there. It's top 10 in my Shanghai experiences, and I've seen it in other bits and pieces. I saw it in a lovely book by Kazuo Ishiguro called ‘When We Were Orphans’, and that's based in the 1920s - and then the 1930s - in Shanghai, so it feels close to the era of the show that we're producing here as well. And he is talking about, even then, the Shanghai Flow in the International Settlement as much as outside of it. And I've loved getting to know this sense of awareness, which says “OK, if you are in my peripheral vision, and I can see you, and you look like you could go first, then I will alter my behaviour, and I will give you the floor, and you can go first. But if you are behind my peripheral vision, or to the side of it, and you can see that I'm going, and I could just go and flow, then I will expect you to alter your behaviour, and let me go past.” And the way that people really do adapt to make sure that everybody's safe means that you can have a real chaos of excitement in the streets that can feel quite daunting to a lot of people - and they feel strange to just stride out into the road and imagine that cars are going to stop - but it's now something I can't switch off, and I'm probably gonna get run over as soon as I go.

OF: Yeah, you've explained that so well, and I think anyone living in Shanghai will immediately recognise what you're describing. Although, to have that definition, it's almost like a secret key. Because I think, especially with someone like myself, I can be very impatient. And I see myself losing my grace slightly when I feel that it's not fair. You know, the British side of me, “I was here first, queue in the right order”. Those moments where you really lose it, you realise “Oh you know what, this is on me, not on anyone else”.

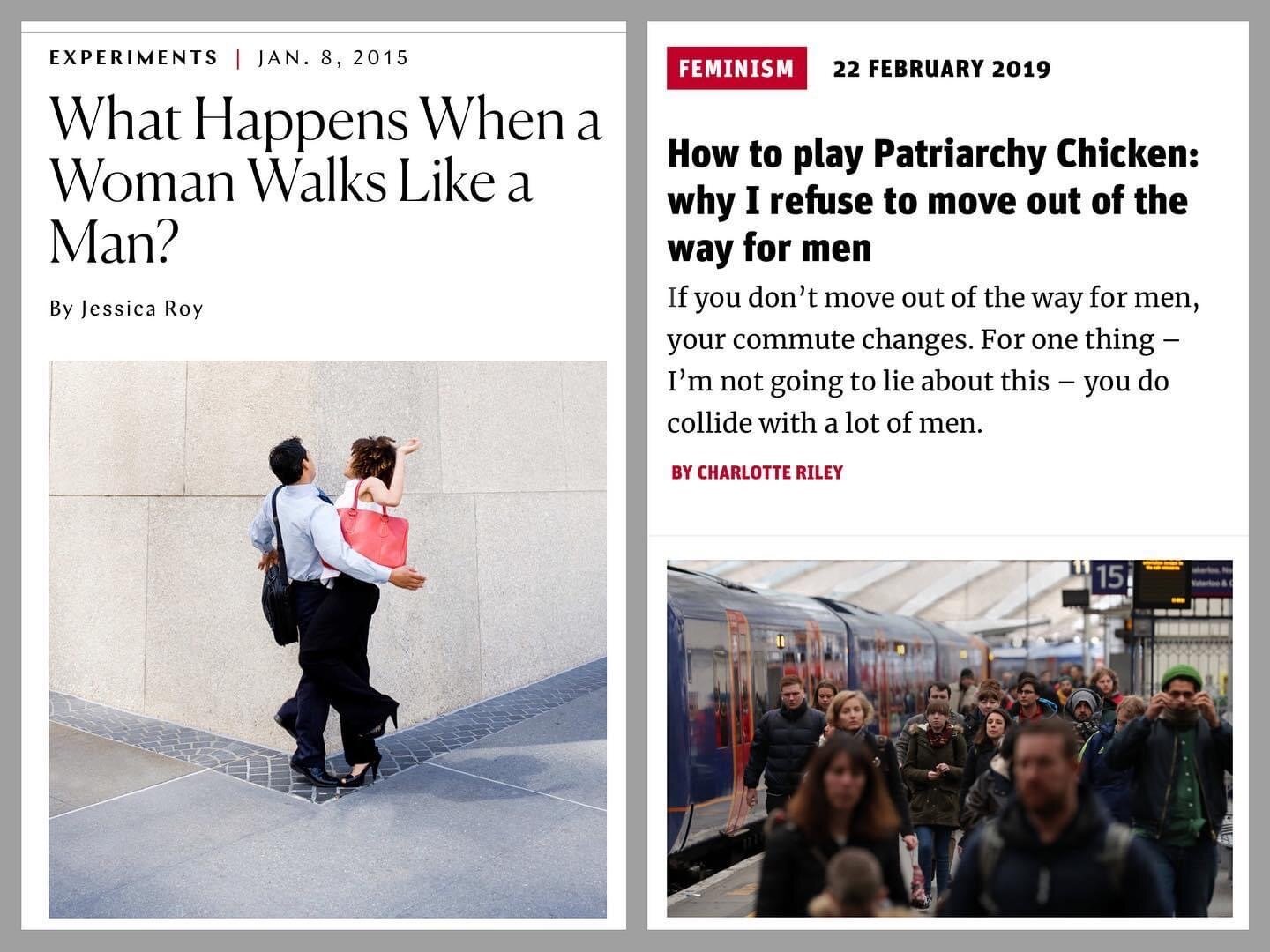

RC: I love that. I think that's such a right acknowledgement. And I think as well in the show, we would feel “How do we navigate this extreme proximity?” And that politeness, you know, like, there's something from time to time in that politeness that can feel a bit like contempt, or that it's an excuse to actually feel riled, or put on the back foot by something, and feel like it's cut up your day. And the flow that you have here isn't something that you'd find somewhere else in the world. In fact, it's the completely opposite phenomenon. I was reading an article recently about women in New York, who've deliberately stopped moving out of the way for men who are walking towards them.

OF: Oh, wow, I love that.

RC: And it hadn't been a thing that I'd noticed, you know. I do all the time, I hop out of the way for people, I yield, I give way, I do that so much. The thing that actually happens is if you stop doing that, you start rugby tackling people. You start, like, American football shoulder barging people, and you need pads, you know. And so it kind of alerted me to this thing that I didn't realise I unconsciously do. And I think I've started to try and unpick that, as well, in my daily life.

OF: I love that idea, just as a sense of everyday liberation. Thank you so much for that, Roz.

RC: Such a pleasure.

OF: Well, let's move on to the second part.

[Part 2]

OF: What's your favourite China-related fact?

RC: There are 10 million Chinese people entering the middle classes every year in China. Which I find to be absolutely astounding, but to make perfect sense. And that when I see the hunger for experiential art, and finding new things to do, I can attribute it a lot to a country that's really saying, like “OK, we're here, this is where we're going, this is what we're going to do, this is how we wanna spend our time.” It's just time travel. It's Shanghai time, it moves so fast, and I feel like you can see that in that fact, somehow.

OF: Mmm. Do you have a favourite word or phrase in Chinese?

RC: I have so many. But I am going to tell you a phrase that was taught to me by James, my boxing instructor: 天下没有不散的宴席 [Tiānxià méiyǒu búsàn de yànxí].

OF: Oh, so explain what it means.

RC: So when I asked James what it means, he grinned his head off and he said “Don’t party, won't finish”! And he threw his head back and laughed. And I was like “What does it mean don’t party won’t finish?” I was like “This is perfect, I've never had a leaving party for anywhere I've ever lived,” under the auspices of the fact that I would then be able to return because I never left. You know, don't have a party, it won't finish, you can always come back. I love it, I love it, I love it. Actually, what it means is, 'all good things must come to an end’ or ‘in the whole world, there is not one party that will not finish’. And it's got such a bitter-sweet longing sense to it. And when I tell people that that's my favourite expression, they all go “天啊 [Tiān’a]!” And everybody can really feel it, actually, when you say that. It's a bit like ‘this too shall pass’.

OF: Wow, that's so lovely. What's your favourite destination within China?

RC: I think my favourite one is 杭州 [Hángzhōu]. And I love that you can get there so quickly and be in the 浙江 [Zhèjiāng] hills, and then walking around and then drinking tea on that mountainside. I really love the way that mountains are transformative here in the way that - you know, they're not necessarily the big mountains, those ones but like - you can still feel the kind of sense of humour, and the work ethic, and the transformative nature of them when you go up and then come down.

OF: If you left China, what would you miss the most, and what would you miss the least?

RC: I really will desperately miss the way in which your food and your daily life is so casual, and on the street, and everybody is on the street. Like, on my street, everyone’s playing badminton, and hanging out, and there's a fruit and you just get it. And, like, people using the street as a playground, as a space to shoot the breeze and compare notes on the order of the day. And so I hope that I'm gonna continue to see that in the UK if I go back, but I’ll really miss that sense here.

OF: Yeah, I actually really agree with you. It's funny, when I first came to Shanghai, you only really see the big streets, the 南京西路 [Nánjīng Xīlù], and the 中山路 [Zhōngshān Lù], and you think “Eugh, who could live in a place like this? It's so big and inhuman.” And then when you live here, you realise that life takes place on the little lanes off the sides of those big streets. And that's exactly what you're describing, I couldn't have put it better. And what about the thing you’ll missed the least?

RC: The thing that I will miss the least is something that I will walk straight into wherever else I go. And in a way, as well, I actually kind of love it for the way that it's changed me. And that is the construction noise. And the way that you experience construction noise here is that you have to let it go. Because the sound of progress is what's going on here. We're building, we're moving, we're going. It's not that I don't hear it any longer, it’s that I am somehow OK with it. And so, while I intensely dislike the construction noise, it has taught me things about myself that I never expected I had the capacity for.

OF: Eugh, your sickening positivity.

RC: It's quite aggressive, isn't it?

OF: Yeah, eugh. Is there anything that still surprises you about life in China?

RC: Everything. I mean, I think if there's something that surprises me, it's that I still have capacity to be surprised. You know, like, “How am I surprised when this is my every day?” You know, every new thing that I learned and every new quirk of the language… My friend Jean taught me this lovely one the other day, it was something about how if people tell you that they met watching the football, then it means that they met when they were in prison. And I was like “How do you even find something like that out?” Like…

OF: That's actually a thing, is it?

RC: Seemingly, yeah.

OF: Oh. Where’s your favourite place to go out, to eat, to drink, to hang out?

RC: I think one of my favourite venues - in the entire world, never mind Shanghai - has to be ALL on 襄阳北路 [Xiāngyáng Běilù]. I think what Gaz has done there is absolutely astounding. The sound system is unparalleled. Whenever I get there, it's the same story every time. I'm like “Do this. Put your bags and coats here. Let's get a drink. Right, now come in here. Now we're going to do a dance”. And then I'm like a four-year-old, I'm like “Listen, can you hear me talking? You can hear me talking, but you can feel the bass, right? You can hear me talking, but you can feel the bass?” It’s like, my friends laugh at me because they're like “Roz, I know. We've done this before. You've literally showed me this five times”. “I know, but I can't believe how good the sound is in here”. And what I love is that any new music that's happening in there, people will say “Oh, but I don't think I like Trap music. I don't like Footwork. I don't think I'm into industrial techno”. But they go in there, they hear that, as soon as you're in front of the DJ, you’re dancing straightaway, because it’s always high quality programming.

OF: Next question, what is the best or worst purchase you've made in China?

RC: I think the best revelation of how to purchase things has been the fabric market. And we have this thing in the company, with all the performers, which is ‘Fabric Market Finery’. And if you're having a house party, or little dinner event for people, then you might say “Wear your best fabric market finery” as if the event itself was somehow black tie. So I went and got a dress made and it's bright orange, and it's made of silk, and it's down to the floor, and it's a copy of a dress that Omagbitse gave me, and it's like the size of a parachute, and it's impossible to ride a bike in, and I love it.

OF: Oh man, I would be so intimidated going out with you, with my jeans and T-shirt. Eugh.

RC: I mean, we love a costume party. We feel like there should be at least one a month. The one that actually happened for my leaving party, the theme of that one was ‘The best and worst of Taobao’. And so everybody came in their Taobao unholy hot mess. And it was like ensembles that had been put together, like a spray of neon and LED lights and silver foil. It was absolutely despicable.

OF: Let's move on. What is your favourite WeChat sticker?

RC: One of my absolute first stickers in Shanghai, let me just show you… here you are. ‘Orange Dancing Boy’, or ‘Orange Boy’. I mean, he's another door opening in a way because then after that, you have to collect every single one that this kid has been a part of. So there’s ‘Orange Boy’, there’s also ‘Green Boy’, there's also ‘Purple Boy’, they're all the same boy. He has different outfits on. He's always dancing, dancing with a joy that is unparalleled by anybody else's dancing. It's completely unselfconscious. I like to think that he doesn't know that he's a WeChat sticker, like, and that there's not going to be that problematic thing of putting your kids on the internet, and then they grow up to resent you. Whenever we find a new one - because he's such an amazing series - I instantly have to send the new one that I found to my great and dear friend, Orange Elephant. Because we have been so obsessed with the portfolio of his works for so long, that as soon as there’s one that we haven't seen before, that’s it, it goes straight to her.

OF: I love it. You've sent me all four of them. And do you know what, I'm gonna blow your mind right now.

RC: Uh-oh.

OF: I actually have two extra stickers to send to you.

RC: Oh my goodness gosh, of Orange Boy?

OF: Yes. Here we go. Here's my first one.

RC: Oh! He’s still wearing the purple shirt!

OF: Well, actually, mine are both the same colour, here’s the second one.

RC: That's impossible.

OF: I haven't seen, actually, the orange and green ones. So you do win, I'm not trying to one-up you here.

RC: Right, no, I mean, it's not a competition. It’s just the furtherance of more amazing stickers. That's what we need in life.

OF: What is your go-to song to sing at KTV?

RC: KTV has completely changed the way that I think about karaoke here. The American style - the Western style, let’s call it - is to, like, take this microphone, get up, prance about like everybody's looking at you, like you have to do some sort of performance, like you have to make it into some sort of big deal or something. When actually you could just sit there, choose a load of songs, whoever's the best one at singing it - or wants to sing it - can sing that song, sit back, do the song to a really high quality level, as if you're playing a game, and then pass the mic to the next person. If you get bored, you don’t have to finish the song. And so, one of the things that we have a tendency to do at KTV is just to rush on in there, get everything on order, and then choose all of the ones that we know. And then somebody can just take it, like, if they want to take it. I think that time that I most ingratiated a room was doing a duet with my mate, Ben, to Bonnie Tyler's ‘Total Eclipse of the Heart’.

OF: Oh, a classic.

RC: Yes. And so I still do have my favourites. But I'm really happy to like, again, just let go of the experience and be, like, just pick any ones we actually know the words to, and we'll all jump in.

OF: And finally, what other China-related media or sources of information do you rely on?

RC: Yes, such a good question. I really love Radii, you know those guys? It’s sort of giving you like the full-circle perspective on loads of Chinese culture. And so it's where I read a huge amount about Chinese hip-hop in particular, but loads of Chinese music, a lot of Chinese metal acts as well. And where I hear about, like, phenomena that are happening on the internet, on Weibo, like, what's going to be the next big thing, and what everybody's talking about, and everybody's responses to this and that. Yeah, it's always written with a real style and wit and humour.

OF: Well Roz, that was great, thank you so much for that. I feel like, even though you've been here for a shorter time than me, you have completely cleaned the floor with your knowledge, and how you've settled into life here in Shanghai. Well, the last question that I ask you - and I ask everyone on this show - is, out of all the people you know in China, who is the one person you'd recommend that I interview next?

RC: I think - being led by a question like that, who's the person you should interview next - I'm going to think immediately of my friend Alan. I don't know if you've met him before, but he used to be a professional tennis player. My story with him was that I was praying to the universe for some absolutely astounding accommodation for a performer who was coming in who's got exquisite taste. And I had been struggling, you know, like putting Airbnbs and various things in front of him, saying “What about this? What about this?” And then, lo and behold, there was Alan, and his lovely wife, with their beautiful apartment. And so, because of the spirit of cross pollination, and Shanghai people always helping one another out, I think he's gonna be my next Shanghailander of choice.

OF: Great. Well, I look forward to meeting Alan. And thank you again so much Roz.

RC: Such a pleasure., thank you so much for having me.

[Outro]

OF: Ever since I recorded this episode last year, I've been thinking about ‘Shanghai Flow’. No-one stops, no-one looks behind them, but everyone keeps going. And so long as you're watchful to the rules of the flow, you should have no reason for aggravation or injury. Right now, I can't believe how much I missing it - even with the potential for aggravation and injury - and when Roz said that she'll miss the street-life of Shanghai when she leaves, I'm sure anyone in China listening to this right now was joining in the chorus “We miss it too!”

I've posted lots of photos online, please search for @oscology* on Instagram and @mosaicofchina on Facebook, or add me on WeChat on my ID, mosaicofchina* and I'll add you to the group there. There's Roz with her keys, including the key to the McKinnon hotel, which is the venue of Sleep No More; there are, of course, photos of inside the venue, where you see the immersive theatre experience. And I asked Roz if she could share any other photos from some of the other immersive theatre pieces she mentioned in our chat. She shared three; one was of a treehouse show called ‘Air Hotel’ that took place in a forest; one was a show called ‘Walking’, which took place on a beach in Norfolk in the UK; and the final one was the world's largest disco ball in a car park. There you go. She mentioned also touring with Circa, this is a contemporary circus troupe from Australia, and I posted a few photos from them too. What else? There are photos from a couple of the articles that mentioned the phenomenon of the women not yielding to men who are walking in a hurry in cities like New York. In one article, this was given the name ‘Man-slamming”. Youch. There are photos of her favourite venue, ALL; there is the phrase 天下没有不散的宴席 [tiānxià méiyǒu búsàn de yànxí], which translates to ‘all good things must come to an end’. The best literal translation I could find is ‘there's no such thing as a never-ending feast’. Oh, and I almost forgot, her favourite WeChat stickers. I’ve posted all of her favourite dancing boy stickers, and I've added the extra two from me, just for good measure. Thank you, WeChat sticker Boy, you are helping to keep us all sane.

Mosaic of China is me, Oscar Fuchs, artwork by Denny Newell, and extra support from Milo de Prieto and Alston Gong. Next week is another good one, I will see you then.

[Easter Egg]

OF: I'm very glad that there's a Brit in my house today.

RC: Really?

OF: Because only a Brit would understand what I did this morning.

RC: Oh, come on.

OF: I had last night's curry for breakfast.

RC: Yeah. Oh wow.

OF: Would you do that?

RC: Yeah, I’d do that. I think curry is a really good breakfast food.

OF: Thank you.

*Different WeChat and Instagram handles were mentioned in the original recording. These IDs are now obsolete, and the updated details have been substituted.