Season 01 Episode 21

Episode 21: The Broadcast Master

YANG Yi - Co-Founder, JustPod

Original Date of Release: 18 Feb 2020.

Yang Yi is a Chinese editor, a broadcaster, and one of the trailblazers in the new world of podcasting in China. He is the host of two podcasts, a culture-themed show called "Left-Right", and a show called "Go! LIVE" where he invites reporters in China to share their eperiences in journalism. And he is also co-founder of the "JustPod" company, which currently produces four original and three branded podcasts.

Yi and I discuss his personal experiences of growing up with broadcast media in China, and he makes some great observations about China's media landscape from the 1990s to today. While our interview was recorded many weeks before the coronavirus outbreak, some of the things we discuss will resonate with anyone observing how the issue is being handled in the Chinese and Western media.

You can also listen to catch-ups with Yang Yi at the end of the interviews with Cassandra CHEN from Season 02 Episode 16 and 'LAODAI' from Season 03 Episode 09.

To Join the Conversation and Follow The Graphics…

View the Facebook Album or the 微博 Article for this episode. Alternatively, follow Mosaic of China on WeChat.

To view the images below on a mobile device, rotate to landscape orientation to see the full image descriptions.

To Listen Here…

Click the ▷ button below:

To Listen/Subscribe Elsewhere…

1) Click the link to this episode on one of these well-known platforms:

2) Or on one of these China-based platforms:

To Read The Transcript…

[Trailer]

YY: Thank you for having me. Oh, I have the opportunity to say these words. Because I watch a lot of English-speaking programming, and the guests say “Oh, thank you for having me”. It’s my first time to say this.

[Intro]

OF: Welcome to Mosaic of China, a podcast about people who are making their mark in China. I'm your host Oscar Fuchs.

Unusual times in China right now. In case you're listening in the future, it’s February 2020, and I'm recording this in Shanghai having returned as planned from my Chinese New Year holiday to Hokkaido. I know many of you listening have been in China throughout the whole Coronavirus outbreak, so I think you guys have gone through a lot more of an ordeal than I have so far. But it was definitely a surreal experience flying back into it. The check-in lady at the airport in Japan even called over her manager who asked us point blank why we're flying to China right now. And even the other Chinese people waiting in line were giving us the side-eye. In the end we simply answered “Because it's our home”. That seems to satisfy everyone, and everything after that went pretty smoothly.

We're now exactly two thirds into Season 01, and I can tell already that the season is going to be split into the pre-Coronavirus 20 episodes, and the post-Coronavirus 10 episodes. So from now on, you can expect me to include little updates on the current situation, just as they relate to the abrupt lifestyle change that we're all experiencing right now in China. But at the same time, I don't want to dwell on it too much. This series was never designed to be a news podcast. These are just human interest stories, which can hopefully be enjoyed whenever you listen to them. And if you are listening to them in real time, with any luck they'll be a nice distraction, especially for those of us in China sitting at home for hours on end in self-quarantine.

So today's episode is with Yang Yi. Yi trained as a broadcast journalists, so his answer to the question about his favourite China news source is definitely one to listen out for. Even though this chat was recorded a good few weeks ago, you can really see the things that he says about the Chinese media and the Western media playing out right now.

Let me quickly talk about Chinese names. Yang Yi is a Chinese name, so this is a surname followed by a first name. That's why I'm calling him ‘Yi’, that's his given name, and Yang is his family name. There shouldn't be too much confusion there, when we say Mao Zedong, we all know that Mao is the family name. The only confusion comes when Chinese people adopt a Western nickname. And in these cases, you don't switch the name order at all. So we've already had Chinese guests like the comedian Maple Zuo in Episode 02. But Yi is my first Chinese guest who doesn't go by a Western nickname. So that's why I'm taking the time now to go through it. And to those of you listening who are rolling your eyes at how elementary all of this is, did you know that there is a place in Europe where they also say the surnames first? Yes, it's in Hungary. So I'm hoping even the eye-rollers out there might have learned something new.

Finally, before we start the episode, let me also warn you that I'm taking you on a bit of an audio quality rollercoaster on this one. The quality in general isn't great, there was an issue in the studio. But just when you're getting used to it, at the end of the recording you'll hear a section that we needed to re-record and splice into the main interview. I wouldn't be mentioned in this if I had any chance of getting away with it. But yeah, you are definitely going to notice this. So please enjoy that nice piece of incompetence.

[Part 1]

YY: Great to see you here. I'm here with Yang Yi, and Yang Yi is a podcaster here in China. And the podcast that you do and produce is called ‘Left, Right’. And you're also the editor of a podcast newsletter called JustPod, right?

YY: Yeah. Podcasts in China is booming now, but it's just starting booming. It's a very emergent industry.

OF: Well, this is what we're hopefully going to talk about today. But before we start, let me see, what is the object that you've brought in today?

YY: OK. Well, I brought - what is it called? - a radio receiver. But actually, this is my newest one. The first radio receiver I used is one that I had since I was maybe three or four years old. That was a very big recorder, it was a combined recorder, tape players and radio receiver, and was produced by the Soviet Union.

OF: Oh, wow.

YY: Yes, but that receiver was very useful, because it could receive a very long distance signal, even from 400 kilometres away. So I don't know how the Soviet Union had the technology to allow the receiver to do this. But actually, it could do that.

OF: So when you were sitting in your hometown, which was where, by the way?

YY: A town in the middle of China called 淮南 [Huáinán], it’s a very small town in 安徽 [Ānhuī] Province. So I could listen to the radio stations from all around world. Voice of America, BBC World Service, the radio station from Taiwan. Yeah.

OF: Wow.

YY: So I think the radio receiver is the biggest part of my life story. Because when I was just a child during middle school, I would write my homework with this radio receiver, and listen to programmes from all around the world. So I remember, I learned about 911 from shortwave radio. So it was faster than any media outlet in China.

OF: Wow. And so I guess this must have been a foundational experience for you.

YY: Yeah, of course. So I think the radio taught me a lot. The world is so big, and people all over the world have a different perspective.

OF: Well, let's talk about your growing up in 安徽 [Ānhuī], what was the kind of media that you were exposed to back then?

YY: Well, during my childhood it was the 1990s, when China already had cable television, and there were a lot of TV channels at that time in China. Because we use a very different system, not as the UK or the US. Because in the US, maybe everyone could register their own TV stations in maybe a small city or small town. But in China, every Province has the television station, like every state in the US has a television station. So they would make a lot of general channels, but they are all general. So they needed to buy a lot of programmes from overseas.

OF: Right.

YY: Yeah. Because they didn't have that ability to produce so many shows. So in the early 90s, I'd watch a lot of shows from overseas, like TV series, cartoons, documentaries. Except news, I could watch all different kinds of shows from overseas, translated into Chinese.

OF: Which means from Japan, Korea, from Europe, from the US…

YY: Yeah, most of them from Japan, US and the UK.

OF: So how does that compare to the way that TV stations broadcast today?

YY: Oh it was totally different, because now China has a very big ability to produce their own shows. And they learnt a lot of different formats from overseas, but they produce by themselves. So I think maybe at this point, younger people, every show they watch from the television set or streaming service is produced by the Chinese. So it's based on China's attitude to the world. In my childhood, shows came from different worlds. So I still could see “Oh the people in the UK live like that. The people in the US live that that”. I was living in a very small town in the middle of China, I didn't have any opportunity or chance to go abroad at that time. So those television programmes opened a door to the world for me.

OF: That's so interesting, because I guess in the decade before that - so, in the 70s 80s - they didn't need as much content. And then today, all the content is from China. So you were in this very special little window between those two periods, right?

YY: Yes, the very short period in the 1990s. Before that, not everybody had a TV set in their house. But 1990s is the time-slot for programmes coming from overseas into China. Like I will give an example. You come from Britain, right? So I'd watch a British television programme when I was around maybe six or seven year old. Actually, I didn't know the programme at that time. But now I know that programme is called ‘Vision On’.

OF: ‘Vision On’, right.

YY: It’s a children's programme, I think it was broadcast in the 1980s. But right here it was in the 1990s. I remember the background music of that show. I remember there is a segment called ‘The Gallery’ which showed paintings from different children. And this was a very small segment, but the music was very good. That show, in my hometown, was broadcast during lunchtime. Yeah.

OF: Give me the story as to you as a child, then. And how does that end up with you becoming interested in broadcasting later on in life?

YY: Well, when I was a very little child, maybe three or four years old, I had the goal to become a journalist in the future. That concept for me, arrived earlier, I think, then for any other child. So when I went to college, my major was in journalism. It was called ‘The art of presenting and anchoring’.

OF: Right.

YY: Yeah, maybe in the US in in the UK, the anchorman is a very experienced journalist. But in China, it’s a separate skill to learn, how to use your voice, something like that. That was my major. When I graduated from college, I just went to the television station as an editor for eight years, until now.

OF: Got it.

YY: Yeah.

OF: And so, in terms of the podcasting scene in China, what kind of characteristics are there about podcasts here?

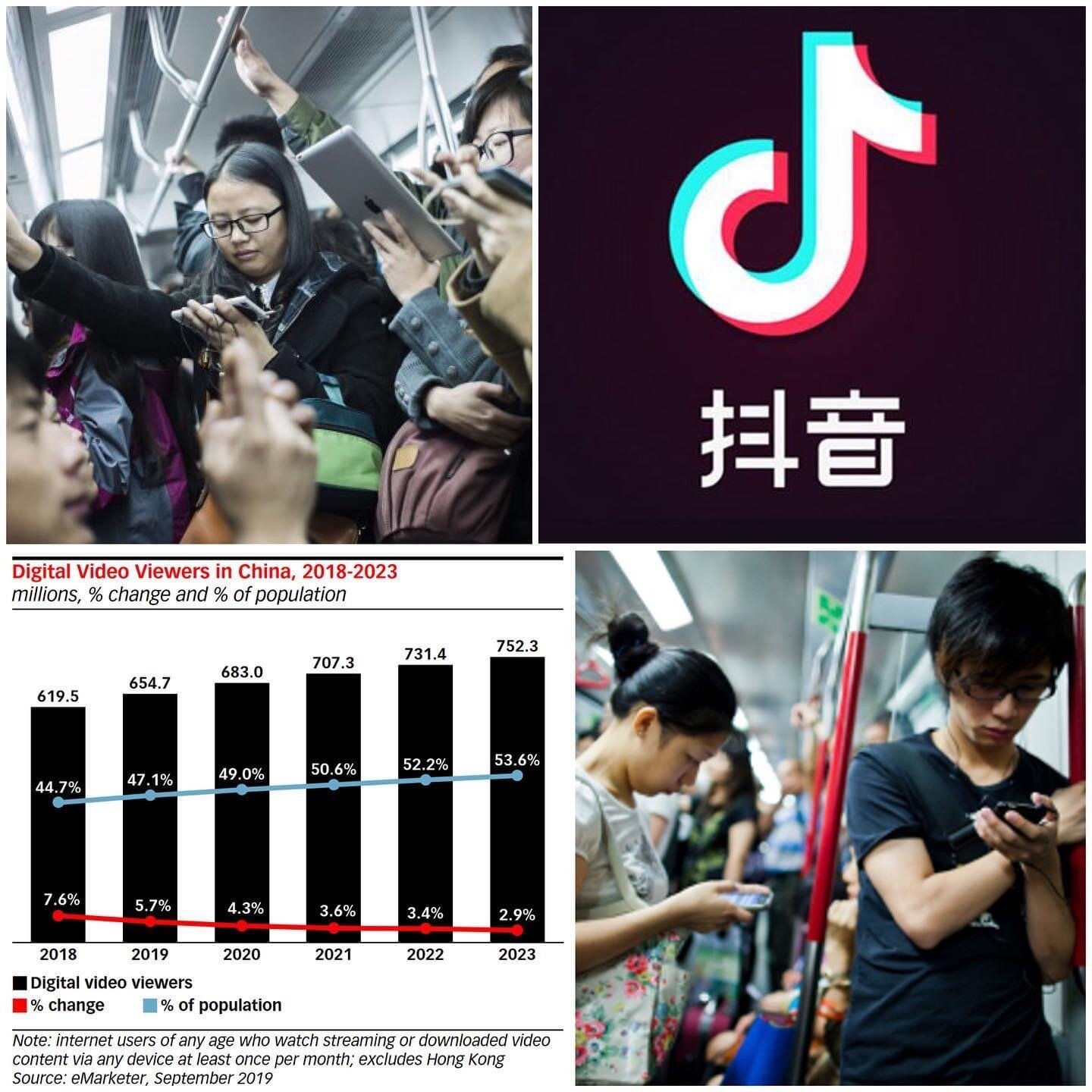

YY: Well, I mentioned before that now in China, podcasting is booming. But I think it's a very early period of that boom. Some people have the habit to listen to something. Because in China, you know, the video, it has a very big audience.

OF: Right. Whenever I'm on the train, I always see people looking at videos on their phones.

YY: Yes, that's right. And you know, TikTok is a big hit in China now.

OF: Right.

YY: So for audio content, it’s very difficult now, in China to let people know “Oh, audio still has a lot of interesting content you can listen to, not just video”. But at this point in many Chinese audience’s mind, they listen to audio content only when they want to have more knowledge. It’s like online education. So a lecture, or very famous celebrity will teach you some point. And you will pay for that. But it's totally different between China and the Western countries, right? Because in the English-speaking podcast world, you have This American Life, you have Serial, you have storytelling shows, right? But in China, there's just one or two storytelling shows, people don't know what is storytelling. And people don't even think “Oh, we could listen to that kind of show”. Because they don't know what it is. After the Cultural Revolution, radio stations needed to reform, right. So at that time, some radio stations in southern China learnt from Hong Kong's radio stations that the announcer - or the presenter - doesn’t need to read scripts. They could, you know, speak freestyle, and use the ordinary people's way to talk. That kind of show was very successful. And then in the whole 1990s, radio stations everywhere learned that model. And, you know, that model is very profitable, because it was very low cost.

OF: Right.

YY: You just need to pay the host. So that became a successful business model, and every radio station learned from that. So radio producers in China's radio stations didn't have any sense about storytelling. Because storytelling is very high budget to produce, right. And they didn't know whether the audience would love that. They didn’t know about this.

OF: Right. But you said there are one or two podcasts now that are doing storytelling. So it's starting to break through now? Or is it still too early to say?

YY: Well I think it’s still early to say. Because maybe these one or two podcasts by themselves are successful. But in the whole media industry in China, they haven’t become a phenomenon. So it's very hard to say they that they have already brought podcasting into the mainstream. No, not at this point.

OF: It's interesting, because if you look at outside - I mean, let's just take the US, for example - where you get a break-out podcast like Serial. But that's on the back of 10 years of slow development, both on the radio and podcasting formats. So I guess it's a little bit difficult to say that China should suddenly catch up, if they haven't had this slow, 10-years progress, right?

YY: Yeah. Because I think we're waiting for our ‘Serial’ moment.

OF: Right.

YY: People, through a hit show, know what is podcasting.

OF: Do you think that you have any big predictions? Or is that too big a question?

YY: Well, for podcasting I think this scene in China will become industrial, it will become professional, and become profitable in the future. Many podcasters in China think podcasts are a space for freedom of speech. But I don't think it is a stable situation. Because in the past years, this medium has a very small audience. And someone - you know, the Big Brothers - don’t focus on you. But if this medium becomes bigger and has more influence, people will focus on you, people will pay attention to you. So that means you won't have free speech anymore in this space. So if you want to keep that kind of free speech in podcasting, I think podcasting will kill itself in China.

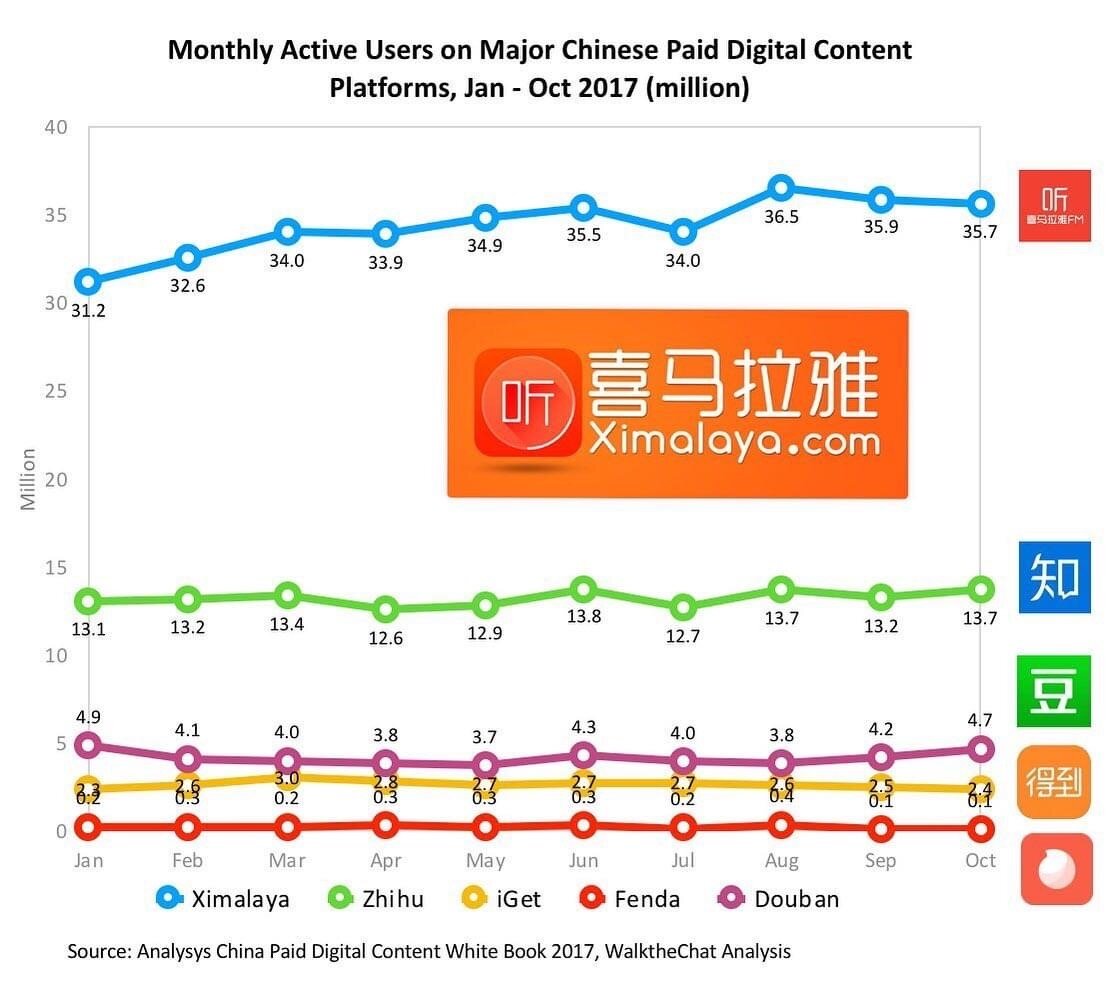

OF: Yeah, that makes sense. And in Western countries, we would use things like iTunes, SoundCloud, what is the environment here in China?

YY: 喜马拉雅 [Xǐmǎlāyǎ] is the biggest one.

OF: Do they themselves try and have editorial control over the content?

YY: Well, they don’t give podcasts editorial control, but they could remove your show, or an episode.

OF: OK. The reason I wanted to ask that question was to lead into my next question, which was about just in general, lifestyle. Because I know that you're a broadcaster, you're a podcaster, but you're also someone who is out there on the LGBT scene as well. Right?

YY: Uh-huh.

OF: But it just made me think you know, how people do try and self-censor, not just on podcasts, but I guess in the way that they live their lives. You strike me as someone who is not really self-censoring the way that you live your life here.

YY: Well, in China, I think, well, first LGBT has their own community. And this community, we don’t need to march on the road, or anything like that. This community is maybe several very close friends, and they will build a WeChat group, and they will talk every day. In the community, I think we don’t have any pressure. We just could talk about our everyday life in that. But to the public, everyone has their different way to face the whole environment. Like me, I have come out. I don't want to hide it. But for many people, it's big pressure. Because maybe someday they will, you know, get married, maybe at the age of 40. Or maybe the age of 45. They have to face the need to get married. They have this kind of pressure. They are gay or lesbian, but their mind is straight.

OF: Oh, I see what you mean.

YY: Yeah. So they still think marriage is the final goal. And they use that standard. So that is the thing… I have a little bit of worry about that. Because they will create a lot of misunderstandings about this whole community. Straight guys will think “Oh, LGBT people don’t take responsibility”. I know they have their own pressure, but I don't think it is a good way to solve the problem.

OF: Got it. Do you think that these two lives will intersect - you know, your podcasting life, the LGBT identity - do you see some interconnectivity in the future for you?

YY: Oh, I truly want to produce an LGBT scene podcast in China. Because this community has a lot of interesting stories to tell. I think it is a very good way to bridge the gap. I think most Chinese people don't know how to date.

OF: Oh right.

YY: They want to date, but the final goal is to get married. So if that is the final goal, they would think a lot about money, life, families, something like that. But I think dating is a very simple thing. Dating is just dating. It’s just chit-chat, it’s just building a connection between two people.

OF: And this style of casual dating is not very common in China.

YY: Yeah.

OF: Wow. And what about LGBT then? What's the future? Or shall we not talk about that?

YY: It’s harder to say than podcasting.

OF: Yeah.

YY: Yeah. Because the Chinese attitude on LGBT is not very stable. It’s flexible. Some years they will become very open to the LGBT community. Some years it will become very closed.=

OF: Yeah.

YY: Maybe now, it’s closed.

OF: Yeah. It's great to speak with you about that. And let's move on to the second part, which is the 10 questions that I ask…

YY: Ah, you sent be the question list before, and it made me think a lot. Because for some of the questions, I’ve never thought about before.

OF: Oh, that's good.

YY: Yeah.

[Part 2]

OF: Question 1, what’s your favourite China-related fact?

YY: OK, in Chinese we call it 中庸之道 [Zhōngyōng zhī dào]. I don't know how to translate it into English. I searched on Wikipedia, it’s called Doctrine of the Mean.

OF: ‘Doctrine of the Mean’, yes.

YY: Yeah, I think it’s the psychology about balance. In my explanation, it means there is nothing too bad or nothing too good. There is nothing truly black or truly white. Chinese medicine uses this philosophy. In Chinese medicine, if you were sick, they didn't try to find a reason behind that. They just tried to keep your body balanced. At that time, when the body got back into balance, you will feel better.

OF: Right.

YY: So I think that is a way for me to explain my life. And when I have any trouble, I think about that.

OF: OK, I'll try to learn that one. 中庸之道 [Zhōngyōng zhī dào].

YY: 中庸之道 [Zhōngyōng zhī dào].

OF: Got it. Well, this is almost the same as Question 2. Do you have a favourite word or phrase in Chinese?

YY: Hmm. So that is the difficult question for me. I usually say 好吧 [Hǎo ba].

OF: That, you hear a lot in China.

YY: Yeah. 好吧 [Hǎo ba].

OF: Can you can you explain that to a non-Chinese person

YY: It’s a little bit like “Oh, that's fine”.

OF: Right.

YY: And the meaning behind it is “Maybe it could be better”.

OF: Uh huh. Right. Well, I'm sure people living in China have heard that pretty much every day since they got here. 好吧 [Hǎo ba], 好吧 [hǎo ba]. If you left China, what would you miss the most, and what would you miss the least?

YY: Oh, miss the most, I think would be efficient life. Yeah. Because, you know, China has 1.4 billion people. Huge population here. So the labour costs in China is very low. Which means there are a lot of people who could give you different kinds of service in China. And it's very cheap. And then the subway. Because I remember in the US, maybe New York city has a very big subway transportation system, but in any other cities you have to drive by yourself, right? I can’t drive. So it's very hard for me to live in the US. But I think ‘efficient life’, what I mean about that is, you can choose your way to live in the city. And no-one can judge it.

OF: Yeah. Is there anything that surprises you about modern life in China?

YY: Well, I want to give the example of TikTok.

OF: Oh yeah.

YY: It's a little bit like Snapchat, but TikTok is focusing on the video part.

OF: Yeah.

YY: Well, I'm a video editor for many years. So I think the applications like TikTok have changed a lot of things. They let people think that video is not a very difficult thing to make, and they can record their personal life. For me, I think this changed a lot. Because people now have the habit to record everything.

OF: And do you think that that will maybe get people more interested in storytelling, because everyone is getting used to telling their own stories?

YY: Maybe, maybe, but I think many people use TikTok just to think of themselves as a celebrity for one minute.

OF: Well, we'll see where that goes, right? I must download TikTok, I still haven't downloaded it, but I find those kind of apps too confusing. What's your favourite place to go, to eat, to drink, to hang out?

YY: OK. So this question will show my boring part. I think usually a friend will recommend some restaurant or coffee shop, and they will bring me there. And at that time, I will give it a score, like “This restaurant is good”. But it doesn't mean I will come back.

OF: Right.

YY: Yeah. Or it doesn't mean it is my favourite. Because I think if you think the place is your favourite, you will go there many times, right? So if you have to say the place I usually go, it’s a small noodle restaurant near my house. I go there every day. But is it my ‘favourite’, I don't think so.

OF: I think that's one way of defining ‘favourite’.

YY: OK.

OF: If you go there that often then I think that counts. What kind of noodles is that noodle shop?

YY: It’s very traditional Chinese noodles, 大肠面 [dàcháng miàn].

OF: Oh, large intestines.

YY: Yeah.

OF: OK.

YY: But it’s pigs

OF: Pigs’ organs, right.

YY: It's very delicious. But I don't know whether it’s the most delicious. But for me, I think it's delicious to eat.

OF: So how often would you go there?

YY: Maybe three times a week?

OF: Oh, wow. Yeah.

YY: Yeah. Because it's very close to my house.

OF: Yeah, yeah. What is the best or worst purchase you've recently made?

YY: Well, I usually buy books, not any other things. If I buy any other purchase, it’s something I truly need to use, like a new microphone, new recorder. But if we talk about books, recently I read a book, ‘The Fifth Risk’, written by Michael Lewis.

OF: That’s fiction or non-fiction?

YY: Non-fiction, it talks about the Trump administration.

OF: Oh, got it.

YY: But it's a very different angle. It just wants to explain how Trump truly influences the US government system.

OF: So you tend to buy the actual books, you don't tend to do the electronic version?

YY: Oh, I tried the electronic version. I tried Kindle before. But finally, I think the physical book is better.

OF: Yeah. I'm the same, but maybe we're dying out, our generation.

YY: Yeah.

OF: What is your favourite WeChat sticker?

YY: So it's about 蛤 [Há]. Yeah, it's a very interesting popular phenomenon in China. It’s related to the former president 江泽民 [Jiāng Zémín].

OF: OK.

YY: And now he's more than 80 years old, and he has a lot of younger fans. Because the younger people think he's interesting. People love him. And we make a lot of different stickers about him. So I showed you one which is about “+1 second, +1 second’. It’s best wishes to an old person, to him.

OF: Ah, so what what it means is, to keep on living, ‘keep living, keep living’.

YY: Yeah.

OF: That’s funny. Wow, I'm glad you explained it, I would not have understood it without that.

YY: Well Chinese leaders are just always poker face. So that's very active. We’d never seen this before.

OF: Oh, how funny. Next question. What is your favourite go-to song to sing at KTV?

YY:

OK, here's a song in Chinese called 最炫民族风 [Zuìxuàn mínzúfēng]. And It’s a miracle song.

OF: OK…

YY: Well, this is not my favourite song, but I think it is my go-to song, you know, at karaoke. Because it's a very good song for warming up.

OF: Ah.

YY: And for me, I think entertaining my friends is a very important thing for me. You know, sometimes when we go to KTV, the first 20 minutes is very embarrassing, right? Someone is picking their own songs, someone is ordering drinks and food, someone is chit-chatting. And no-one is focusing on singing. So this song is, you know, how do you say it?

OF: It kind of makes everyone feel energetic, or..?

YY: Yeah.

OF: Right.

YY: So it's a very good way for everyone to pay attention to you.

OF: Right.

YY: I just hate that embarrassed half hour.

OF: Yeah.

YY: I think “Oh, I should break this situation. I need to do something”.

OF: You’re a very useful person to have a KTV, I think. And finally, what other China-related media or sources of information do you rely on?

YY: Well, if Chinese media, I think 财新 [Cáixīn] Media is the best choice. But it’s in the Chinese language. It's just professional news, like FT and Bloomberg in the English world is still very useful.

OF: Right, so it's like the equivalent of FT, right?

YY: Yeah. And I think the financial news is a good point in China to open very small door for news.

OF: Yeah, well said.

YY: And if you talk about English, in my mind I think foreign media for China is very useful, because you have freedom of speech. So you have an opportunity to cover a lot of issues that Chinese media can’t cover. But a lot of Western media surely have a stereotype on China, among Chinese issues.

OF: Yeah.

YY: And I am still an editor and journalist, I know that feeling. It’s “Well, I have a storyline. I want to introduce someone to fill in that blank”. And I think sometimes it relies on some stereotype. If they have the opportunity to get some new discovery, they don't want to go into that. It is “Oh, that's that's not my storyline”.

OF: Yes. Yes, because it doesn't fit the story that I want to write.

YY: Yeah, but I am a big of foreign media, actually. But I still find their Chinese coverage has some problem like that. So that's a little bit, you know… For me, it's a combination.

OF: Yeah. I like that. And I like that you can look at 财新 [Cáixīn], and then you can look at foreign media, and then you can find that somewhere in between there is something called ‘the truth’.

YY: Uh-huh.

OF: Thank you so much for your time today, Yi.

YY: Oh thank you Oscar.

OF: Really, really interesting, we covered quite a few different topics here. And the last thing I will ask you before you leave is out of everyone who you know in China, who should I interview in the next season of Mosaic of China?

YY: OK, I nominate Chu Yang. She's one of my friends. And she's a very interesting girl, because she is tough. So I think she would be very interesting. There are some kind of very challenging and tough persons in China who care about world issues, feminism issues, and she was a journalist. So she’s maybe experiencing some issues about journalism in China. So I think she has a lot of topics for you to talk about.

OF: That sounds great. I'm interested and intimidated at the same time. Thanks Yi.

YY: Thank you for having me. Oh, I have the opportunity to say these words. Because I watch a lot of English-speaking programming, and the guests say “Oh, thank you for having me”. It’s my first time to say this.

OF: You said it very well, thank you too.

YY: Thank you.

[Outro]

OF: So the main thing to unpack from today's episode is the word 蛤 [há] that Yi casually mentioned when describing the 江泽民 [Jiāng Zémín] sticker. This 蛤 [há] means toad. I won't go into all the details here, but you can look up ‘toad worship’ on the internet to find out more. I kid you not. It really reminds me of Episode 16, when Nini talked about llamas. Sometimes the simplest of things have a hidden complexity in China, especially when it comes to evading the censors. The 江泽民 [Jiāng Zémín] WeChat sticker is of course on social media. If you're in the WeChat group, you'll have seen the original sticker. To join, please add me on my ID: mosaicofchina* and I'll add you there myself. And otherwise, you can see screenshots of the sticker on Instagram at @oscology* and Facebook at @mosaicofchina.

Apart from the sticker, there are lots of other images online this week. We have Yi with his object, his radio. And he was back in his hometown of 淮南 [Huáinán] over the Chinese New Year, so he was able to take a photo of the original radio made in the Soviet Union, which he mentioned. There's also a couple of photos from 淮南 [Huáinán] itself. Yi described it as a very small town in our chat, but it didn't surprise me to discover that it has 2.3 million inhabitants. I’ve posted Yi’s phrase in Chinese, 好吧 [hǎo ba], which means something like “well, alright then”. That's in contrast to 好的 [hǎo de] which is a more emphatic way of saying ‘yes’ or ‘OK’. There's also the logo of 'Vision On’, the programme from the UK that was aired at lunchtimes in 安徽 [Ānhuī] in the 90s. 'Vision On’ actually originally aired on BBC One in the UK in the 60s and 70s - so, a long time before it came to 安徽 [Ānhuī] - and it was originally designed specifically for children with hearing impairments. It's a little bit before my time, but I've definitely heard of it, and I'm sure most of the Brits out there have too. Speaking of programmes, Yi mentioned that there are a couple of storytelling shows breaking through in the China podcast space at the moment. The most famous of these is definitely 故事FM. If you can understand Mandarin, I would really recommend it. And the exciting news is that Yi himself has put his money where his mouth is. Since we recorded this interview together, he has quit his day job at the TV station and is now a full-time podcaster. More than that he has also co-founded China's first podcasting company called JustPod, which now produces a bunch of different shows. So I'm really excited for Yi and I can't wait to see where he - and the other China podcasters like him - takes this medium in the future. There are lots of other images, but I am taking too much time, so I'll just let you discover them for yourselves.

Mosaic of China is me, Oscar Fuchs, artwork by Denny Newell, and extra support from Milo de Prieto and Alston Gong. I am still planning on being here next week, and I hope the same goes for you.

*Different WeChat and Instagram handles were mentioned in the original recording. These IDs are now obsolete, and the updated details have been substituted.