Season 03 Episode 06

The details below are for the REGULAR version of this episode. For the PREMIUM version, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Patreon (outside China) or 爱发电 (in China).

Episode 06: The Child-Development Champion

Barbara POPPELL - Co-Founder & Director, Bright Futures

Original Date of Release: 11 Oct 2022.

They say it takes a village to raise a child. That doesn't just include parents, teachers and care-givers, in China it often also includes grandparents and domestic helpers. Indeed, the raising of kids impacts impatient childless podcasters whose everyday lives also casually intersect with children, whether they like it or not.

We all could use a little help, especially when it comes to knowing when to follow the best practices of our parents, and when it's time to break certain cycles. That's where today's guest Barbara Poppell steps in. And having lived exactly half her life in China, she can also speak to the global village of family and community services.

The episode also includes a catch-up interview with Louise ROY from Season 02 Episode 06.

Season 03 is supported by Shanghai Daily - the China news site; Rosetta Stone - the language learning company; naked Retreats - the luxury resorts company; SmartShanghai - the listings and classifieds app; and JustPod - the podcast production company.

To Join the Conversation and Follow The Graphics…

View the Instagram Story Highlight, the LinkedIn Post or the Facebook Album for this episode. Alternatively, follow Mosaic of China on WeChat.

To view the images below on a mobile device, rotate to landscape orientation to see the full image descriptions.

![Barbara Poppell: When we're talking about behaviour and families in China, the 阿姨 [āyí] needs to be involved.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d40122274f3720001d9543b/1665135358458-UC8RL7ANKA6IXJC8OQNI/CN+11296+s03e06+Barbara+POPPELL+D+General+Episode+Image.jpg)

![Barbara Poppell's favourite China-related fact: When she first lived in Shanghai in 1999, the turning lanes of the 延安高架 [Yán'ān Gāojià] were bicycle lanes.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d40122274f3720001d9543b/1665135360643-J6Z0TL87R1XWL5V1ALCI/CN+11299+s03e06+Barbara+POPPELL+E+Q01a+Fact.jpg)

![Barbara Poppell's favourite phrase in Chinese: 很有意思 [Hěn yǒuyìsi - Very interesting].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d40122274f3720001d9543b/1665135361371-YC3F378PLX1Y4091WJO2/CN+11300+s03e06+Barbara+POPPELL+F+Q02a+Phrase.jpg)

![Barbara Poppell's favourite destination in China: 厦门 [Xiàmén], because it reminds her of Southern California.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d40122274f3720001d9543b/1665135362298-5GQT4LRCP0TJGUL96VH9/CN+11301+s03e06+Barbara+POPPELL+G+Q03a+Destination.jpg)

To Listen Here…

Click the ▷ button below:

To Listen/Subscribe Elsewhere…

1) Click the link to this episode on one of these well-known platforms:

2) Or on one of these China-based platforms:

To Read The Transcript…

[Trailer]

BP: Being 18 years old and taking a child development course was the best birth control I ever had.

[Intro]

OF: Welcome to Mosaic of China, a podcast about people who are making their mark in China. I’m your host, Oscar Fuchs.

We’ve had a week off for the so-called ‘Golden Week’ holidays here in China, so welcome back. It’s been another tricky time for us here, as COVID continues to make life extremely unpredictable in this part of the world. I personally know of six families who have found themselves trapped in various locations around the country because of sudden outbreaks. It is ongoing, it is repetitive, it is exhausting, it is… Enter your word of choice.

In case you were thinking of a word beginning with ‘f’, then so was I. And the word is one I’ve already mentioned in this intro, it’s ‘families’, because today’s episode is about families and raising kids. And when it comes to another ‘f’ word, namely the ‘facts’ about how to raise children, that’s where the answers are both everywhere and nowhere to be found. So talking to someone who is able to curate and personalise all the contradictory sciences and pseudo-sciences that are out there is fascinating, not just for parents but also for non-parents alike. Being a non-parent myself - and I might add, a non-parent who is convinced they would make a terrible parent - I have no fear asking all the stupid questions that parents might be too embarrassed to ask themselves. You’re welcome!

[Part 1]

OF: Barbara, lovely to see you.

BP: You as well.

OF: You are Barbara Poppell, am I saying that right?

BP: That is correct.

OF: And how would you try to encapsulate what it is that you do?

BP: It’s taken me a long time to get it down to one sentence.

OF: Right.

BP: I operate a family and community services company.

OF: Well, we'll figure out what that means.

BP: Exactly.

OF: Before we do, what is the object that you have brought that in some way represents your life?

BP: Yes, I brought a pillow box, a Chinese pillow box.

OF: Oh I see.

BP: I actually got this pillow box when I was 14 years old. And I'm much older than that now. And inside is where we keep all of the loose money from the different parts of the world I've been.

OF: Nice.

BP: It kind of encapsulates a lot of who I am. I lived in China for a big portion of my life, and also travelled the world. So this is just a little bit of everything that I am.

OF: I like the metaphor. Because of course, it is a very Chinese thing.

BP: Right.

OF: And then enclosed within, is a bunch of international experiences.

BP: Yeah.

OF: Do you know its actual functional use?

BP: Yeah, they used to be used as pillows, and to keep all of our things that are most important to us nearby.

OF: Right. So you would keep your valuables there, so no-one could steal them from underneath your head.

BP: Correct.

OF: I didn't actually know that.

BP: Yeah.

OF: And you said that you got that when you were 14, right?

BP: Yeah, my story in China starts in 1998. My dad got a job to work for a manufacturing company here in China. And my parents have been living here ever since. So they've lived in Shanghai, and now live in 苏州 [Sūzhōu]. And a lot of times people say “Isn't it nice to live where you grew up?” And I tell them “I don't live where I grew up”. I geographically live where I grew up. But this city is not the same.

OF: Yeah, isn't that well said. Anyone who has been in Shanghai has lived in 14 different cities.

BP: Absolutely. The only thing that's really the same from when I was a kid is what's now called Shanghai Centre. But when I was a kid, we called it The Portman. And it was the centre of town because you could get into any taxi and say “波特曼 [Bōtèmàn],” a taxi driver will understand that, and you'll get to a place where you can then go wherever you need to go. Then when I moved back as an adult, I would say “Let’s meet at The Portman.” And people would be like “What's The Portman?”

OF: Yeah.

BP: Nobody knows where The Portman is now. And so for me, these little things of my life don't exist anymore.

OF: Right. And this is kind of connected to what you're doing these days. You were here as a child, I guess at 14 you're still a child.

BP: Yeah.

OF: And you did say what you did. So what was that ‘elevator pitch’ again?

BP: The elevator pitch for what we do is, we're a family and community services company. So that company is called Bright Futures.

OF: OK. And let's break that down.

BP: Yeah.

OF: So what is it that you do?

BP: I think it's easier if I say how we started.

OF: Yeah.

BP: I moved back to China in 2011. My emphasis was in early detection and early intervention for kids with special needs.

OF: Right.

BP: This is what I loved. Then, investors in one of the schools that I was working with went bankrupt. And I suddenly didn't have a job, in October. Which is not a great time as an educator to start looking for a job. Because school starts in September. So any school that's looking for a teacher in October, it either means they're not a great school, or they've had something really bad happen.

OF: Right.

BP: So do I look for a new job, or do I start my own company? I was going to a friend's wedding in the U.S - it was going to be a flight from Shanghai to Chicago - so I decided I'm going to message some families, and see if they're looking for support. So I messaged them all before I got on the flight. I let it be, I had to turn off my phone, I couldn't think about it any more. And when I landed, out of the seven families I messaged, five of them said “Yes, we're looking for support.”

OF: OK.

BP: So then I was like “OK, I'm just going to do this”. And that's where we started. Just me supporting families that had kids with special needs. Then that evolved into us doing workshops in the community. And I brought on other team members to help support that as well. There's actually a lot that families and community members don't know about raising children. We're currently all using these tools that we have from when we were a kid. We all turned out OK. Now we have this different set of tools that we can use. But how do parents get access to these tools? Are they reading 100 books to try and figure this out? Are they on the internet all the time? In the U.S. where I'm from, there are community groups that will help filter this information. Here in Shanghai, we don't have access to these things as readily. In the special education world, we look at how each child is different, and we tailor programmes to each child. But this is actually true of all humans. Everybody's different. So a tool that might work for one child isn't going to work for another child. So one parenting style might not work, and another style might work. This also is the same with teaching. So it's about having this flexible use of different tools, different skills, to build up and be able to use.

OF: Got it. Well, as we're about to talk about parents, this is where I have to admit that I am not a parent. And it is reminding me of another episode of the podcast I did last season, with Louise Roy who is the person who referred you to the podcast. So let's hear what Louise said about you.

[Start of Audio Clip]

Louise ROY: I am going to recommend Barbara Poppell. She is in child development, and has an amazing perspective on how parents can help kids becoming their best little people that they are.

[End of Audio Clip]

OF: So my interview with Louise was all about childbirth, and it's almost like she's passing the baton on now to you.

BP: Yes.

OF: Since we're talking about child development. Tell me, how do you know Louise?

BP: I know Louise through her children.

OF: Oh right.

BP: Yeah, I would also like to take this moment to say I also don't have children.

OF: Oh, right.

BP: Yes. I like to tell families that being 18 years old and taking a child development course was the best birth control I ever had. It's not off the table. It's just I really know what's going to happen when kids come. So I like to remind families that I don't talk from experience, I talk from science. This is what science says, and then you're going to do with it what you please. And I actually had feedback from a parent once who said “I actually prefer that you don't have kids, because I don't feel like you're judging me. And I'm not comparing myself to you as a parent.” I mean, I always tell families when we're talking about really difficult things - and I know that what I'm asking of them is a lot of work on their end - I always joke with them, like “Don't worry guys, I'm gonna have a kid one day, and you guys can all laugh at me and be like “Barb, do you remember that one time when you said “Just do this one thing.” Now how is it for you, when you actually have your own kids?”” So what I'm doing is serious work, but it's also fun work. At the end of the day, always at the centre is kids. We have to have fun with it. I can laugh at myself, and I want families to be able to laugh at themselves too.

OF: Right.

BP: Raising a little human is ridiculous. And that goes for kids with special needs, or typically developing kids. Everybody needs a little bit of help. A lot of families really worry about biting, hitting.

OF: Biting and hitting.

BP: Biting and hitting, these are two behaviours that we see a lot in young children.

OF: “Young" meaning how old?

BP: We can see it as early as six months old, and it's still developmentally appropriate up until about four and a half years old.

OF: OK.

BP: You might start to get a little bit worried at about four and a half years old, if we still have this happening. And biting and hitting come from an inability to express our basic wants and needs. And it all comes back to our brain. This is my favourite thing to talk about, is the brain. I can ask you what I ask most of my families, which is “When was the last time you learned about the brain?”

OF: I can't even remember. I think I had very simple biology lessons. Then that's it.

BP: And yet, that is what's in charge of all of your behaviours.

OF: Yeah.

BP: And we don't know about this thing. So what's happening for a kid who's biting or hitting in early years, is they're just using the part of their brain that is working the strongest. Because the part of our brain that says “Hey, I don't like it when you take my toys,” this part of their brain is not working yet. Now, is it a behaviour that we want to encourage? Absolutely not. We then want to teach appropriate behaviours. But then how do we go about doing that? This is where things get fun.

OF: Yes, we're talking about social skills here. The child's natural impulse, and to what extent is that natural impulse something which we should encourage - that’s just them being themselves - and to what extent do we have to put on top an overlay of social skills? As a parent, that must be a daily battle.

BP: Absolutely. And I think this is what most families are going through. “Am I doing the right thing, am I doing the wrong thing?” What I always tell families is "You're keeping your child alive, you're keeping yourself alive. These are the two most important things. Everything else from there, we can work on. The relationship goals you have for you and your kid, their behavioural skills, all of these things. How do we find a balance that works for your family?” This is really what it's about.

OF: So I'm guessing that that is what you do. You'll get the consultation, they'll tell you the issue, and you'll give them some kind of tools that will allow them to start to manage - or to reverse - whatever behaviour they're talking about. “Step one: do this; step two: do that.”

BP: This is what families want. I don't have the answers for you. If I had the answers, Oscar, I would not be here.

OF: You’d be a multi-millionaire.

BP: I would be a multi-billionaire living on some wonderful beach. This is the difficulty. It’s that I also want to be really honest with families, there is no easy fix. A joke that Louise laughs very hard at, is that in childbirth after the baby came out, there wasn't a guidebook on how to use this baby. It was a placenta that came out after.

OF: Now you're putting an image in my head.

BP: Yeah, I know.

OF: Which is a very painful one.

BP: Everyone’s welcome for that. I know. This is why Louise laughs, everybody else feels a little squeamish with that joke. But it's the truth of the matter. So what I like to do with families first is: “Here's the general information that you need. This is ‘Child Development 101. What age do you think that the brain is actually ready to read and write? It's a lot later than were teaching kids to read and write. When is the appropriate age to be expecting of kids to wait? It's much later than we're expecting of kids right now.”

OF: Oh really?

BP: Yeah, this skill begins at around three and a half years old.

OF: Oh.

BP: This is when it starts developing. When we really see a kid who can resist something for a while - if they've been in an environment that has fostered this skill in an appropriate way - we’re looking at six or eight years old. So it's a long time. And yet, we're telling kids “Don't touch it, don't do it.” And now we're adding all of these stress hormones going through the brain.

OF: Oh.

BP: This is actually what's feeding these neural pathways, and these neural connections. So now we have stress and anxiety that are being built within.

OF: But the person who reaches this age of development at eight years old, at least they've heard the “No" throughout the last three or four years, and then they can click in, and suddenly it makes sense? Or would you say just don't do the whole “No, no” thing, and then just switch it on when they're seven or eight? What's the answer?

BP: That is such a good question. And it's a question that a lot of families ask: “Well OK great, you've told me this thing, but now what do I do with this information?”

OF: Right.

BP: So then it's about saying “OK, if you have something that's here on the table that you don't want a child to touch, you just say “Yes this is really yummy, we’re going to eat it later, and we're going to wait together.” And we talk about what waiting means. And it might mean the entire time that we're waiting, we're talking about waiting.”

OF: Oh.

BP: Because this is how we're teaching this skill of waiting. It might also mean that I'm going to take it and put it in a different place where we can't touch it. Because now we're still developing the skill of waiting, without the automatic reinforcer being right there in front of us.

OF: And without the negativity of the “No, no, no”, you're switching it to a more positive kind of language.

BP: Exactly.

OF: Right.

BP: So this is very different than how I was raised.

OF: Oh yeah.

BP: It was different than how you were raised, it's different than how most people were raised. So coming up with these ideas - and these skills - takes a lot of work, and a lot of time. And if you say “No, no, no, no, no,” that's all right. Now what are we going to do about that, now that you've noticed “Oh, I'm saying “No” a lot. OK, what can I do to change? How can I then make it better moving forward?” If we beat ourselves up for what happened in the past, we're just making things worse.

OF: Yeah.

BP: We can always look and be like “Wow, that could have gone better. How are we going to make it better for the next time?”

OF: Yeah. OK, well we're talking about how you consult with parents of children, why don't we switch it to teachers. Do the teachers themselves come to you for help on how they deal with children?

BP: We do it kind of both ways. Teachers come to us, but it's more effective when we go into schools. So we go to kindergartens, we go to primary - even secondary - schools as well. And talk to them about all these kinds of strategies that we're talking about for parents, but in the classroom. I was a classroom teacher, it's not easy.

OF: No.

BP: You have so many things to worry about.

OF: And then above all that, the education side. But you have to deal with the actual kids themselves at the same time, right?

BP: Exactly. I was just in a school last week and was talking with a teacher who's struggling with one of her students. And I told her, I said “He's going to learn math. He's going to learn to read. If you can give him the skill of being able to ask for help" - which is really what it boiled down to - “This is a skill he can carry with him the rest of his life”. We're really looking at these soft skills. “Cool, you can add, and you can read, and you can write. But what makes you actually a successful human in the business world are these soft skills.”

OF: Yeah.

BP: Being able to talk to people, being able to make a compromise with them, all of these skills are not the focus in most academic programmes.

OF: No, right. It’s something which they just let you pick up.

BP: Yeah.

OF: So would you be advocating for actually lessons on learning social skills?

BP: Not lessons, but having this be a part of the curriculum. Going back to the example of this teacher I just worked with, she said “But I talked to the kids about how we ask for help, and when we do it.” I said “That's great. But we all learn best when we can apply our skills. So that means you have to find times throughout your week, where you're ‘giving the lesson’. This is where you're finding these moments to do it.” This is a lot to ask of a teacher too, who has so many other things to do. So this is where looking at social emotional skills, having a lesson for it is going to be a great foundation, but it's not enough.

OF: No.

BP: It has to be as they’re happening.

OF: Yeah, that's the thing. It has to be in the moment.

BP: Right, when a kid has done something wrong, and we ask “What did you do?” And they can tell us what they did. And we can ask “Why did you do it?” Sometimes they know, sometimes they don't. And you say “What should you have done?" They can almost always tell us what they should have done.

OF: OK.

BP: They know it. The problem is, it’s our brain. Our brains are not wired to be fully mature when we're in kindergarten, middle school, and secondary. Which is hard and exhausting.

OF: Well, it’s the exhausting part of it which makes me think that you will always be in business. The fact that this isn't an easy fix, that's why someone like you can have quite a busy lifestyle here in Shanghai.

BP: Yeah, I mean we do. And this is part of what we love, it’s that we do lots of different things. We work with families one-on-one, we work with families in groups, 阿姨 [āyí]s as well.

OF: Do you know, in three seasons of this podcast, I think we've mentioned 阿姨 [āyí]s but we've never really defined them, for people who don't know who they are. Why don't we just take a step back, what is the 阿姨 [āyí]?

BP: So an 阿姨 [āyí] in Chinese means ‘Auntie.’ That's what the word means. And what an 阿姨 [āyí] is, it's a domestic helper, if we look at it for people outside of China. People inside of China know that it's so much more than that. An 阿姨 [āyí] can be anything from a nanny, to a babysitter, to a housekeeper, it can be so many different things. The 阿姨 [āyí]s that I'm working with usually are taking care of children.

OF: Right. Because I would have an 阿姨 [āyí] who comes once a week and cleans the house. And that's a different kind of 阿姨 [āyí] to the ones who were always around the family, almost like another member of the family, right?

BP: Exactly. They are an aunt.

OF: Yes. Good, well there you go. So when we're talking about behaviour and families, the 阿姨 [āyí] has to be involved, right?

BP: Absolutely. We are asking of these women to help take care of our children. And yet most 阿姨 [āyí]s have not completed compulsory education. Here in China, compulsory education is nine years. Some of them have, some of them haven’t. What I find with a lot of 阿姨 [āyí]s is: “If the kid is happy, then the family will be happy. So how am I going to keep this kid happy?” Keeping a kid happy - as most parents with young children will know - does not mean that they're getting the skills that they need to be successful humans.

OF: Yes, exactly. Well, I mean, there are what I would call ‘expats’.

BP: Right.

OF: But when I say ‘expat’, I'm thinking about a very particular kind of international family, where perhaps they have created a bit of a bubble between them and the local culture, and the children are raised with an amazing amount of privilege. What happens to that child when the child grows up, right?

BP: Exactly. This is something that was very evident in my childhood growing up here. We had a wonderful 阿姨 [āyí] named Claire, who was solely in charge of cleaning the house. But was a wonderful human being as well, who loved my brother and I, and we loved her back. And my mom would regularly threaten to fire her - in a joking way - because she would clean our rooms for us, she would do our laundry, and my mom would say “Who is going to marry them if you don't let them learn these life skills?”

OF: Yes.

BP: She said “Claire, you're not going to move with them, and take care of them. They have to learn these skills on their own.”

OF: I love your mother already.

BP: Yeah. And so there's this paradox that we have, where there's an over-taking-care-of, and an under-taking-care-of in some ways as well. And so when we're looking at 阿姨 [āyí]s, what are a lot of the skills they need? 阿姨 [Āyí]s - just like parents, and teachers, and other people interacting with children - need a new set of skills to talk to children. 阿姨 [Āyí]s need those skills too. Otherwise they're running around saying “No, no, no, 不可以 [bùkěyǐ], 不可以 [bùkěyǐ], 不可以 [bùkěyǐ],” all of these things, right? They also need to understand, it's OK to set boundaries and limits for kids. And how do you do that, where you can also communicate with the family that you're working with, on “This is how I'm helping your child develop skills that they need.” Right? It's a lot for them to take on.

OF: We’re talking about this in the context of these expat kids. When you interface with Chinese families, do you see the same things universally? Or do you see a specific cultural element on top?

BP: So with Chinese families, a lot of times we have, you know “Oh well we must respect our grandparents, we need to do what our grandparents say”. And yet, we also want our kids to be able to stand up and say how they're feeling. These are two conflicting worlds that a lot of families are coming into. So it's about then teaching a balance. And I think that this is across a lot of cultures. How do you respect the people in your life, and still advocate for your basic wants and needs? I'll give you an example. If we have a child who doesn't want to wear a jacket when they go outside to play, we can get into a huge screaming battle about this. I’ve witnessed thousands of them. Grandpa says “You have to put on this jacket before you go outside.” And the kid is saying “I don't want to put on this jacket.” Nobody's stopping and saying “Why don't you want to put on this jacket?” We're stuck in this conflict of “I'm telling you to do something, and therefore you must do it.” And the child trying to find control.

OF: Yes.

BP: Really is what they're trying to do.

OF: Yes.

BP: They’re trying to find their voice. So then how do we come together to solve this, to bridge this? There are a lot of people who are starting to see that these conflicts are unnecessary. The world of ‘positive discipline’ is really on trend here in China right now.

OF: Would you say in main cities like Shanghai? Or would you say across China in general?

BP: Across China in general.

OF: OK.

BP: The education system is trying to fold it in a lot more. There are a lot of parents that are coming and getting training for positive discipline. And a lot of grandparents. The big challenge here in China is, how do we keep true to our culture? We're not trying to change a culture, we're trying to change a set of skills.

OF: Yes.

BP: You still want kids to be able to say “This is too much for me. I don't want to put on a jacket, because I'm hot”.

OF: Yeah.

BP: And let them be able to say those things.

OF: Right. Without being counter-cultural to filial piety and respecting elders.

BP: Yeah, we can have a balance of all of these things. The challenge - and this is not a China challenge, this is a human challenge - is “I have to leave my history at the door, if I'm going to change”. Understanding what the last 50 years was here in China, is very different than the last 50 years in the United States, very different than they were in the UK. So understanding that this helped you survive 50 years ago. And so it's “How do we then all work together to make sure everyone feels respected?” This is the most important, no matter where we are in the world. If I'm going to do good, I have to feel good. And respect here, is where we start. And once we can build that - for grandparents, parents - we also need to make sure that that's happening for the child as well.

OF: Yes. And to feel in this one cohesive caregiving team, while at the same time have a difference of opinion now and again, right?

BP: Yeah. And it's, your feelings are your feelings. I can't change your feelings. I can change how I view your feelings, but I can never change your feelings. You have to change the behaviours that you have with your feelings.

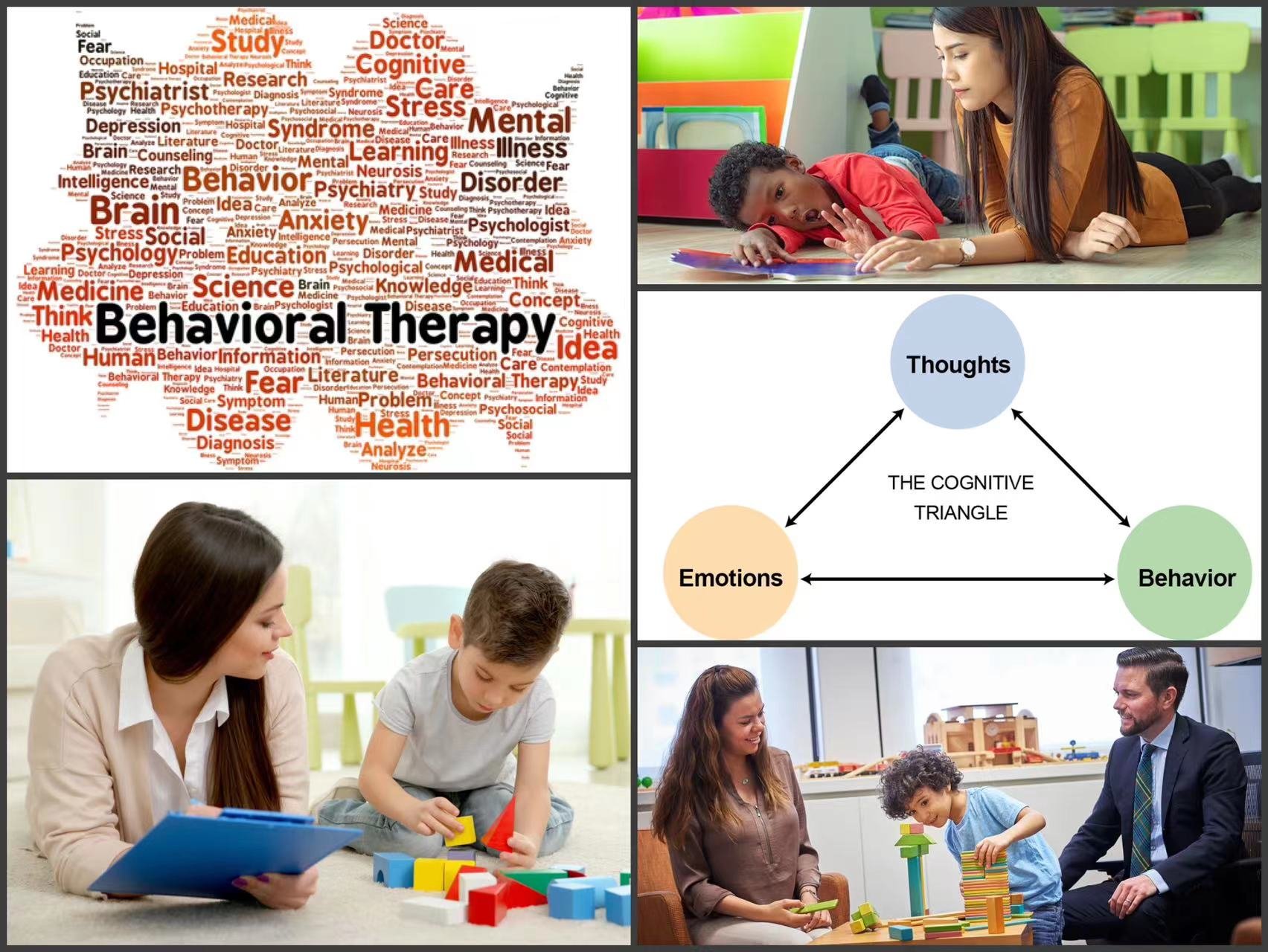

OF: Yes. Well this is now coming into the realm of behavioural therapy, right?

BP: Yeah.

OF: This is what we’re talking about. Like, what is the situation of behavioural therapy in China? Has it changed a lot in the same way that everything else has changed?

BP: Yes, when I started university, the board certified organisation for behaviour therapists was just in its infancy, it was just starting. Occupational therapy, speech therapy, physical therapy, these are the services that most people think of when they think of therapeutic services. Behaviour therapy is something a little bit different. In China, 10 years ago there were two board-certified behaviour therapists in the entire country.

OF: OK.

BP: Now there are a couple of thousand. One of the things I really appreciate about being here in China is that, when something is shown to be evidence-based, China gets on board. “This works, so let's do it.” And there's a big behaviour community that's really starting to grow and develop here. It gets trickier when we're looking at some of these bigger behaviour changes. Like when we're looking at an eight, nine or ten year old who might have explosive behaviours - meaning that they're screaming or throwing things or hitting - we work really closely with mental health counsellors. Because there's a certain point, it's a very fine line between “Am I building a skill?” or “There's some other things that need to be unpacked.”

OF: Right. The parents do one thing. OK, that's not working, let's go to someone like you. And then when it's something which is beyond your realm, it will get passed on to the next specialist, right?

BP: Correct.

OF: Which I think is a natural way, you're not going from A to Z, you actually going through those courses without too much input from outside, right?

BP: Exactly. And I also think that it's helpful to some families - this again is a global issue, but we really really see it prevalent in China - that when we seek additional services, it means that we're admitting there might be something wrong.

OF: Yeah. Something wrong, and I'm too weak to fix it.

BP: What we're really asking parents to do, is to go into work without any job training. And if you mess up on the job, it affects the project forever.

OF: Yeah. No pressure.

BP: No pressure.

OF: How would you feel that working in this realm has affected you personally?

BP: Hmm. Anybody who has had a conversation with me for longer than an hour knows that this is the reason I get up in the morning. I love making a difference in families’ lives. Whether they have a two-month-old baby - and they don't know what to do with this little blob of cells that has just formed and come out of their body - all the way to a 16/17-year-old child who's on the autism spectrum, and needs skills to be able to be a functioning member of society as an adult.

OF: And my next question would be: “And how does that leak into your personal life?” But the more I talk to you, the more I think “Actually, is there a personal life?”

BP: No personal life. I'm that person who, back in the good old days, when I would go to happy hour, and teachers would be there, and they would, you know, kind of nuzzle up next to me, and be like “So you know, I have this one kid in my class…” And that's how almost all of my happy hours went for about six years, before I started doing this is a business. And then even as a business, I just love talking about it. I like to say I'm a nerd. For fun, I read journal articles and things about brain science.

OF: Well, I think many parents listening would be very glad that you are that nerd. I mean, I am not a parent, and yet I've learned a lot from you. So thank you very much for that, Barbara. I wish you good luck as you continue to build your team.

BP: Thank you.

OF: And let's move on to Part 2.

BP: Sounds good.

[Part 2]

OF: Right then, the 10 questions question. Now I'm in control.

BP: This is my favourite part of the podcast.

OF: Oh!

BP: I listened to all the episodes. I love this part.

OF: OK, everyone, listen to Barbara. But you've put pressure on yourself now.

BP: I know.

OF: Because I need to have good answers.

BP: I've thought about these answers so much.

OF: Oh, great.

BP: My husband and I this morning sat down and we were like “OK, so is this my real answer for this? We went through, and I even got his perspective, and he was like “I don't think that's your favourite Chinese phrase”.

OF: Oh.

BP: And I was like "You're right. It's not!”

OF: How funny.

BP: So there's been a lot.

OF: OK, so Question 1, which comes from Shanghai Daily: What is your favourite China-related fact?

BP: So my favourite China-related fact is actually a Shanghai-related fact.

OF: Uh-huh.

BP: Under 延安高架 [Yán'ān Gāojià].

OF: That’s the motorway we'd say, you'd say ‘highway’ right?

BP: Yeah, the ‘elevated highway,’ yeah.

OF: The ‘elevated highway, yes.

BP: So underneath we have our good old regular road, and then to the side of that is what's now turned into the turning lanes, if you're going to go on to the rest of the roads. When I first moved to China in 1999, those were bicycle lanes. And they were packed full of bicycles. And this was the busiest part of the road. The car parts…

OF: Very few.

BP: Very few. But that bicycle lane was so packed. So I love driving down the road now, and being like “Remember when this was all bicycles.”

OF: Yes. Of course, we all know about how bikes turned into cars.

BP: Yeah.

OF: But then to have that physical representation - where you reminded each time - that’s very nice.

BP: Yeah, it is.

OF: Next question, which comes from Rosetta Stone: Do you have a favourite word or phrase in Chinese?

BP: I do. My husband reminded me actually that this is my favourite phrase. My favourite phrase is 很有意思 [hěn yǒuyìsi].

OF: 很有意思 [Hěn yǒuyìsi].

BP: It's "how interesting”. And I say this in English all the time. I feel like it's a phrase that fits with the mood perfectly.

OF: Oh, it fits you entirely. You're a nerd. And everything is 很有意思 [hěn yǒuyìsi].

BP: Yeah.

OF: Oh my god. Were you always the school nerd?

BP: I wish I was.

OF: Ah.

BP: Probably why I'm such an advocate for educating kids the way in which their brains function, is that I was not educated in a way that my brain functioned. I like to have time to read, and deep dive, and go down a rabbit hole. And we don't set that up for kids in schools.

OF: No.

BP: There are lots of timelines and deadlines and things like that. So I always felt like I was just rushing to the end, when it came to school. In my graduate programmes, that's when I really felt like I became the true nerd. My true self got to show.

OF: 很有意思 [Hěn yǒuyìsi].

BP: It’s a good one.

OF: It is a good one, you’re the first person to say that. Next question, which comes from naked Retreats: What is your favourite destination within China?

BP: This one took me a long time to think about, but what I've decided is that 厦门 [Xiàmén] is actually my favourite place.

OF: 厦门 [Xiàmén], right?

BP: Because I'm originally from Southern California. And I feel like 厦门 [Xiàmén] is the Southern California of China.

OF: It’s laid back, right?

BP: Very laid back, palm trees everywhere, but we’ve still got a city. We're still doing some business. And we still respect that we need to take a break sometimes.

OF: Ha. That's true, yeah, I've only been there for one long weekend. But I definitely felt the different energy there, especially coming from a frenetic city like Shanghai.

BP: Right, right. And I really liked that in 厦门 [Xiàmén] I can go down for a weekend, and just be at the beach. Or I can go into the city, and be in a mall. Or I can go and do workshops at a big international school. Or have this connection, everything is there in 厦门 [Xiàmén]. It's quite nice.

OF: You said you're from SoCal, whereabouts in Southern California?

BP: I'm from Orange County.

OF: Yes.

BP: Home of Disneyland.

OF: Yes.

BP: That’s where I'm originally from.

OF: There you go. We got this far in our conversation without me asking you that. Nice, shout-out to 厦门 [Xiàmén].

BP: Yeah.

OF: If you left China, what would you miss the most, and what would you miss the least?

BP: What I’d miss the most is logistics.

OF: Yeah, things just work here.

BP: They just happen.

OF: On the scale of China.

BP: Yeah.

OF: Yeah.

BP: I can order something from the other side of the country, and it'll get to me in a week. That's amazing.

OF: Yeah.

BP: If I try and do that in the US. I'll be lucky if I get it in two weeks.

OF: Yeah.

BP: Right? The thing that I'll miss the least… It’s actually interesting, because I've left China before. I was here as a kid, and then went back to the U.S. and then came back. And what I didn't miss was the close proximity, the pushing.

OF: Ah.

BP: So as much as I love the convenience of the Metro, I hate going on the Metro. I don't enjoy having people push me, and be in my space. I don't like it at all. COVID has been great for this. It's been a lot better going places. But it's something that I don't miss when I’m gone.

OF: Yes, different cultures have different notions of personal space.

BP: Yes.

OF: I feel it too.

BP: Yeah.

OF: Is there anything that still surprises you about life in China?

BP: The thing that surprises me is actually not China itself, it’s other people's views of China. Parents say “I don't like it when people look at my baby in the stroller.”

OF: Oh right.

BP: Here in China, this is a thing that happens quite a bit, right? They do it to each other. And I can understand why families don't like that. “I want you to ask first.” And I have to remind myself “Number one, this is their first baby. Number two, maybe they haven't been here in China for very long.” To know that this is a big celebration piece for families.

OF: Yes. But then it's not just China, like I can imagine if we were in Italy, there’s the whole ‘bambino’ culture as well, right?

BP: Yeah, there's something everywhere.

OF: Next question, which comes from SmartShanghai: What is your favourite place to go out, to eat, or drink, or to hang out?

BP: It's like when you're in The Oscars, and it's the reel of all the people that have passed away from the year, this is how I feel when you ask this question. There are so many places I used to go to that just don't exist anymore.

OF: Yeah.

BP: They’re gone. And so, you know, with the convenience of 外卖 [Wàimài] and things like that, my favourite place to go out is my house. If I'm going for a drink, I do love craft beer. So anywhere that there's a really good craft beer, I'll go drink it.

OF: Next question, what's the best or worst purchase you've made in China?

BP: The best purchase I've ever made in China is actually an experience. I love the things that Sarah from Pinyin Press does.

OF: Ah.

BP: Yeah, she's an amazing designer. And she does screen printing classes. And so I've attended a couple of those. It's my favourite purchase here, because I do not see myself as an artistic person. And yet, I leave that class with something that looks like I could sell it in a store.

OF: Right.

BP: It makes me very excited. So to me, that's one of the best purchases I've ever had.

OF: Very nice.

BP: Yeah.

OF: There’s a nice connection too, because in Season 01 of Mosaic of China, there was an episode with Nini Sum, who herself ran the first ever independent screen printing studio in China...

BP: There we go.

OF: …Where she talked about this way that art can be given to people who think they don't have any artistic skills.

BP: Yeah.

OF: OK, next question. What is your favourite WeChat sticker? Here it comes. OK. Now, do you know that this has been used before?

BP: Oh has it?

OF: Yes. Explain what's going on.

BP: So there's a little dog, sitting at a table, in a room that's on fire, and he just says “This is fine.”

OF: Yes.

BP: And this has just been the sticker that I've used the most in the last two years.

OF: Oh, this is the COVID sticker.

BP: Yeah, it really is.

OF: That's it. We're all plastering the face of this demented dog on our faces.

BP: Yeah.

OF: Smiling, going “Yeah, this is fine.” It's not fine.

BP: It's not fine. And yet we still have to deal with it. So here it is.

OF: Yeah. It's actually very cute, I do use this lovingly. Next question, what is your go-to song to sing at KTV?

BP: I've been singing karaoke for as long as I can remember.

OF: Back in the day, when in China, that was the only entertainment available.

BP: Absolutely, we would be ten 15-year-olds in a KTV room singing at the top of our lungs.

OF: Yeah.

BP: Like, this is what happened. My favourite KTV songs are power ballads, which are the worst to have. ‘Black Velvet’: “Black Velvet and that little boy’s smile,” that's the one. And ‘Alone,’ those are my two favourites.

OF: ‘Black Velvet’, I know. ‘Alone’ is which one?

BP: By Heart. “Till now”…

OF: Oh.

BP: “…I always got by on my own”. Some big notes in there, some real fun. Not great in a small KTV room.

OF: You're living up to the reputation that Brits have, with loud-mouthed American people now.

BP: That's me, 100%.

OF: I love it. And finally, and this comes to us from from JustPod, which is the studio we're in right now…

BP: Nice.

OF: What or who is your biggest source of inspiration in China?

BP: The source of my inspiration genuinely is the families that I work for. The kids who I get to help affect change in their life, either directly or indirectly. To know that I can be here in China and that I can help, this is a huge source of inspiration for me.

OF: And then now and again, do you have the chance to see people a couple of years after you've worked with them? You randomly meet them on the street, or they actually make a point of coming to see you. Do you have those experiences?

BP: Yeah, I do. Working here the last 10 years, I've gotten to see some kids grow up here. That's really cool for me to get to see.

OF: Yeah. There you go, you don't need to be a parent yourself. You are a parent to all these different children.

BP: Oh, I’m glad I'm not a parent to all these children. The best part of my job is I get to leave the children.

OF: That’s true. That's why I love being ‘Uncle Oscar’.

BP: Yeah. ‘Aunt Barbara’'s real fun.

OF: Yeah. Thank you very much, Barbara.

BP: You're welcome.

OF: I hope that people listening will take some solace that they are not doing everything wrong, they’re not doing everything right: just do the best you can.

BP: Yeah, everybody's just doing their best. If we're a society of people who are just trying to do the best they can, we’ll be in a good spot.

OF: Thank you. And before you leave, I want to ask you, who would you recommend that I interview in the next season of Mosaic of China?

BP: I'm gonna recommend that you interview Dr. George.

OF: Dr. George?

BP: Dr. George, yes. He is a mental health counsellor. And he is…

OF: Oh, I think I know him, George Hu.

BP: Yes. ‘Dr. George’ is what he goes by. We, oddly enough, met in a group chat for Californians.

OF: Ah.

BP: Yes. And then found out that we were both kind of in the same field. Have met each other once in person, but mainly all just via WeChat, and supporting the same kind of community. And he does so much work advocating for the importance of mental health.

OF: Great. It's obviously an extension of what you've been talking about. And I can now also see how Louise's story merges into your story, which now is a natural pathway into George’s story too.

BP: Yeah, it is, it is. All three of us are a part of 'family services’ that I talk about. And we all have so many other people on our teams that help support that as well.

OF: Yeah. Thank you. And if there was one question that you would ask Dr. George yourself, what would you ask him?

BP: I would ask how his role as being a parent has influenced his practice as a mental health counsellor. Has that changed for him once he became a parent, or is it still the same?

OF: Yes. That's the perfect question that you would ask him.

BP: I would.

OF: Thank you again.

BP: You're welcome.

[Outro]

OF: There you have it, I hope this episode has been of service to both existing and future parents, as well as to those of us who are standing on the sidelines scratching our heads and wondering how anyone does it. The full-length conversation this week was massive, I think there was over 20 minutes of extra content in my chat with Barbara. So if you’re still sitting on the fence about whether you should be listening to the PREMIUM version of the show, now is a good week to subscribe on Patreon or Apple Podcasts Subscriptions internationally, or on 爱发电 [Àifādiàn] in China. Just go to Barbara’s page on the Mosaic of China website for all the links. Here are some quick clips from today’s extended show:

[Clip 1]

BP: I use all my patience with other people.

OF: And then you come home, and you're a monster.

BP: I'm a monster to him.

[Clip 2]

BP: How do you react? Are we reinforcing this behaviour without knowing it?

[Clip 3]

BP: Over 300 kids, I've helped them learn how to use the toilet. And you're helping one child learn how to use the toilet.

OF: Ah

[Clip 4]

OF: Would the outcome be that that person would say “Sorry” and mean it?

BP: You opened a Pandora's Box when you said the word “Sorry.”

[Clip 5]

BP: I don't want to have to be there with you all day, every day.

OF: No.

[Clip 6]

BP: So the brain is getting what it needs, in a socially inappropriate way.

[Clip 7]

BP: They look at me. And I say to them “What do you want me to do?”

[Clip 8]

BP: But I can look at a kid and be like “Oh, you're bouncing off the walls.”

OF: Yeah.

[Clip 9]

BP: The definition of a behaviour is an organism’s interaction with their environment. You're an organism.

OF: Oh, thank you.

BP: You’re welcome.

[End of Audio Clips]

OF: Because today’s episode is quite long, I’m going to keep my outro short. Check out the website or social media for all the graphics alongside today’s episode, including information about how you can contact Barbara and Bright Futures. You’ll also see Barbara’s favourite WeChat sticker there, which - in case you had been wondering - was the same one chosen by the drag artist ‘Cocosanti’ from Season 02 Episode 05.

Mosaic of China is me, Oscar Fuchs, with artwork by Denny Newell. We mentioned the person who referred Barbara to the Mosaic from last season throughout the episode, it was of course Louise Roy, the childbirth and lactation expert from Ferguson Health. If you still haven’t heard Louise’s original episode yet, then you need to listen to that one immediately after you’ve heard the quick catch-up with her coming up after the music. And I hope to be back with you again next week.

[Catch-Up Interview]

OF: ‘Ello, Louise.

LR: Hey Oscar.

OF: Louise, you came in last season to talk about…

LR: Boobies, bellies and babies.

OF: And it turned out to be one of the listener favourites of the season.

LR: Oh, good.

OF: Yeah, it was illuminating. But do you know what I felt most badly about was that, we didn't talk much about you in that recording. At the time that we recorded, we were booted out of the studio, because we already had gone a little bit over. So they were quite right to kick us out. And they were quite right to be annoyed, because they had a guest there waiting as well. So anyway, the point being, we rushed it, and I couldn't really talk about you as a person. So maybe now is a chance to make it up to you a little bit. Just to ask you what has been life like for you since we did the recording? Which is a year ago, possibly more.

LR: I'm not entirely sure. My concept of time in the last two years - since COVID, basically - is…

OF: Fluid.

LR: Fluid. Like, sometimes I feel like I'm tripping because I don't know how it's two years later. And then also, how am I not 500 by now, in the last two years? Yeah, what has life been like? Well, you know, I've got two kids. I think I mentioned that much. They're 11 and 9. And you know, life has to keep going on. A very interesting thing was, the other day I asked them if they remembered life before COVID, thinking they were going to be like “Oh yeah yeah yeah, we used to do all these things.” And they said “No, not really.“

OF: Really?

LR: Yeah. So it's been interesting to parent in this time. You know, for some families that's just the way it is. But for many it was like “This is not what I signed up for.” And that's a big lesson in the reality of: we don't actually sign up for something. You know, the world happens around us, and we adapt and adjust and pivot. But that lesson in “Oh, this is my new normal” has been tough for a lot of people.

OF: Yeah. Yes. “No, you're not in control of your life.”

LR: Yeah, exactly. And you know, I was just discussing this this morning, that we can plan and prepare and have ideals, but they have to go hand in hand with flexibility.

OF: So people listening to this now will be hearing this alongside the episode of the person who you referred, which was Barbara, Poppell.

LR: Exactly.

OF: So have you had much to do with Barbara?

LR: We've both been incredibly busy. I think the fact that so many people haven't been leaving - they are here - both of our industries have been thrust into ‘hustle mode’. So we haven't had a lot of time to hang out. I mean, I spend so much of my day explaining how everything about what a person is doing is normal. People come to me with so many problems that aren't actually problems. It's just our society has told us all this time, it's a problem. And we come to our own health as women, with expectations that are so wrong.

OF: Yeah, right.

LR: And it needs to be corrected.

OF: So how often then, would you be in a position where you are saying to a client “No, that's just normal”?

LR: Oh, every single day.

OF: Yeah.

LR: Probably 80% of the time. The big part I'm thinking of is as a lactation consultant. I do a lot of problem solving, there are problems that we have to work around to get babies feeding, and people having enough milk, and all the things that can be problematic. But the reality is that most of the time people come to me for a one hour consultation, 50 minutes of that is them just listing the things they're concerned about, and me explaining why it's normal. And most of the time, at the end of it, parents say “You know what, I'm so glad I came, because that's what I felt. But I just kept worrying about it. And people kept getting in my head.” And they had that instinct that everything was fine to start with, but it was just being undermined.

OF: Yeah.

LR: And this is where I could go full circle and say that on our episode together, I said my favourite WeChat sticker was the “Google it, you lazy ****”.

OF: Correct.

LR: But actually, now I tell parents don't Google it, just 'Lou-gle it.’ Call me. Call Lou.

OF: ‘Lou-gle’.

LR: I don't want to have to say “Go research this,” because…

OF: …You’ll find yourself in some weird corner of the internet.

LR: Exactly. And it's just really unfortunate that all of this access to information has had an opposite effect.

OF: Right. Yeah, we thought that the Internet would be a marketplace of ideas, and then the correct ideas would just gravitate towards the top. But that's not what happened, right.

LR: No, we filled it with cats and porn.

OF: Well, going along the lines of ‘normal’, you have a brand called ‘Not Broken,’ right?

LR: Yeah. It's kind of my tagline all the time, saying “Your baby's not broken, your body's not broken, your brain’s not broken. This is normal, and let's just nudge it in a way that we can be even better, and even happier.”

OF: Well, watch this space. Louise, thank you so much for being on the show last season, thank you for coming in today…

LR: You’re welcome.

OF …And hopefully in the future, too.

LR: Thank you, Oscar.