Season 03 Bonus: The Bridge (CGTN)

The details below are for the REGULAR version of this episode. For the PREMIUM version, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Patreon (outside China) or 爱发电 (in China).

Bonus Episode

Mosaic of China with Oscar Fuchs - 'The Bridge'

Original Date of Release: 27 Jun 2023.

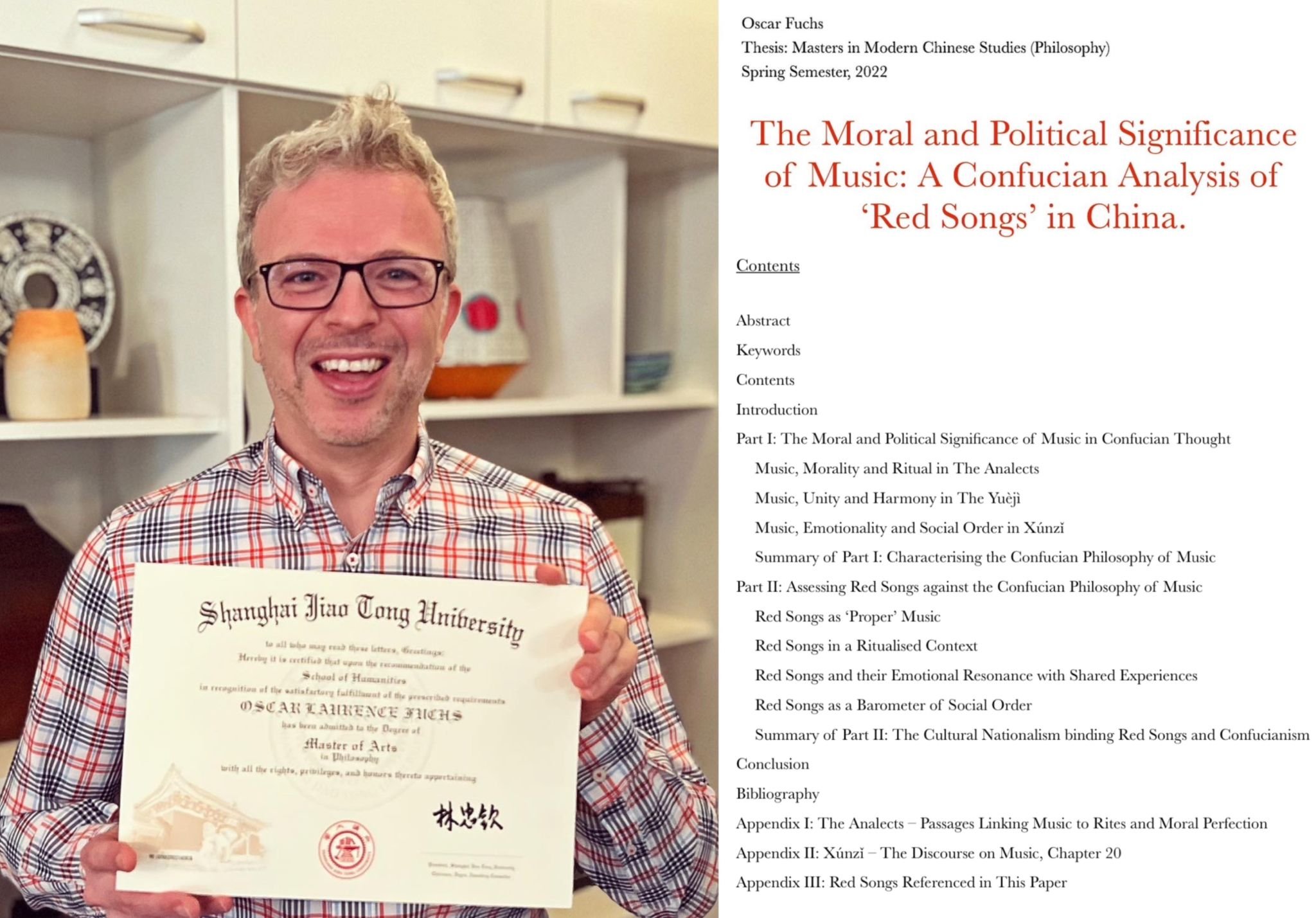

Around the same time as launching Mosaic of China, I also embarked on a period of study at Shanghai Jiaotong University, starting with a course in Mandarin language followed by a Masters in Modern Chinese Studies. In today's special bonus episode, I discuss a little of what I learnt with Jason Smith and Beibei from CGTN's 'The Bridge' podcast. In our chat recorded earlier this year, we talk about Chinese philosophy, as well as some of the similarities and differences between life in China versus Singapore.

A big thanks to Jason and the team at The Bridge for giving me permission to share this edited version on the feed for Mosaic of China. The original full episode can be found here.

Season 03 is supported by Shanghai Daily - the China news site; Rosetta Stone - the language learning company; naked Retreats - the luxury resorts company; SmartShanghai - the listings and classifieds app; and JustPod - the podcast production company.

To Join the Conversation and Follow The Graphics…

View the Instagram Story Highlight, LinkedIn Post, or the Facebook Album for this episode. Alternatively, follow Mosaic of China on WeChat.

To view the images below on a mobile device, rotate to landscape orientation to see the full image descriptions.

To Listen Here…

Click the ▷ button below:

To Listen/Subscribe Elsewhere…

1) Click the link to this episode on one of these well-known platforms:

2) Or on one of these China-based platforms:

To Read The Transcript…

[Trailer]

OF: Oh my god, I was being indoctrinated!

[Intro]

OF: Welcome to Mosaic of China, a podcast about people who are making their mark in China. I’m your host, Oscar Fuchs.

If you heard the last show, you will already know that I’ve been down with COVID-19 for the first time. I was very sluggish and low energy for a couple of weeks, and then I managed to go travelling for a short trip, and now I’m back in Shanghai and feeling almost back to normal. So the good news is that I’m finally back to work on the next few episodes coming up. The bad news is that I’ve fallen quite far behind in my production schedule, so today is not a full episode. But I have some bonus content in the form of an interview that I did on another podcast called The Bridge, which is hosted by Beijing residents Jason Smith and ‘Beibei’. The Bridge is a show produced by CGTN, one of the state-run news networks here in China. So it’s not quite as independent as Mosaic of China, and I decided to hold my tongue a little bit at some points. But in general it’s a fun show, they do a good job, and we cover some different ground from other interviews that I’ve done recently. So I’m happy to share an edited version in the feed today. The full version was a lot longer, so if you want to hear that please head to The Bridge wherever you listen to podcasts, where I think you’ll find my episode was released some time back in April.

As for Mosaic of China, there are still 8 great episodes left in Season 03, so while you’re listening to today’s show I’m going to head back to work, and I hope to see you back here soon with Episode 23.

[Main]

JS: Today we are joined by a fellow podcaster who interviews folks who are making their mark in China. In August 2019 Oscar Fuchs launched ‘Mosaic of China’, a lighthearted English-language podcast. Oscar has also co-founded a Singapore-based headhunting company. He's lived three years in Japan, one year in Germany, six years in Singapore, three years in Hong Kong, and seven years in China's mainland. He is a British national and currently resides in Shanghai. He earned a Master's degree in Chinese Philosophy from Shanghai 交通 [Jiāotōng] University. We'll never hear the end of it from Beibei now. Welcome to The Bridge, Oscar.

OF: Oh my god, you’ve done your research.

JS: My goodness!

OF: Who is that guy you're describing?

JS: You lived in Germany; you lived in Japan; you lived in Singapore; you lived in Hong Kong; you lived in Shanghai. Why travelling all over the world like this, is just your passion?

OF: Maybe I'm running away from something, right?

JS: That's not what I was indicating, but…

OF: I guess it's a passion. It's not something I ever planned, honestly. I happen to have landed in different situations where I just sort of went with the flow. And if an opportunity arose, I said “Yes”. Where others might have questioned it, I just jumped in. That's certainly what happened with most of those moves. It sounds really cool when you look back over the 20 years, but each of those moves were pretty much unplanned.

B: I want to ask, can you tell other people who might be thinking about travelling and actually living in foreign countries, what to fear and what not to fear? Were you ever fearful about going to new places?

OF: I wasn’t. I always liked the adventure. And I'm sure there are many people listening who feel the same way. But I mean, yes, there are always nerves involved. I think if you didn't have some nerves, you'd be a bit of an idiot, right? You have to have some trepidation. I think, if I was to give any advice, it would be ‘people are people are people’.

B: Umm.

OF: Yes, there are different languages; there are different customs; there are different foods. Even once you know a language, there are different ways of communicating which you might find strange - maybe too direct, maybe not direct enough - but then when it comes down to it, everyone is pretty much the same. There are people who can stress themselves out thinking “Oh, how am I gonna fit into Japan? How am I gonna fit into China? I'm gonna have to learn all the customs, I’m gonna read all the books.” I mean, yes, you can do that. And it's very respectful to do it, it's respectful to understand it. It's not necessarily the secret to your mental health and wellbeing to try and adopt everything. You can learn a lot about other cultures. But actually you end up learning a lot about your own culture, just how it's mirrored through a different culture.

JS: Absolutely.

OF: You can say “Oh, I always thought that's how you do things, and now it's being done completely differently. Maybe I've been complacent”. If somebody asks you “OK, how's it done in your country?” then you've got to think about “Yeah, how the hell is it done in my country? And why do we do that?” And that's half of the fun of this cultural communication. It's not just about learning about other cultures, it’s about recognising the weird things about yourself.

JS: Yeah, absolutely that's true, it goes both ways. I want to change the topic a little bit. You did a Master's degree dissertation on Confucianism and music. Could you share with us a little bit about what are some of the points that you made in that dissertation? And how is music part of Confucianism?

OF: This is where I start to get nervous because it was a Master's degree, not a PhD guys.

B: It's part of rites, right?

OF: That's what I would start with. Because we have one idea of what music is these days. You know, we have our mp3 players or we go to music concerts. That's not what music was back in the days of Confucius. In the days of Confucius, you had no access to music, apart from if the local Lord put on some kind of ceremony. Where they would drag you from your farm - from what you were doing - and they would make you listen to this concert, which basically was just a variety of different bells. We're talking very, very simple music. What Confucianism saw music as was a way to bind people together through a shared sense of morality and harmony and social cohesion. And then later on the other Confucian thinkers, they also extended that to a political value and a tool for political solidarity and obedience. Obedience and power, especially in the Imperial era of China. So that's really what Confucianism thinks of as music. It definitely has to be absorbed in this ritualised context, and it has to foment this shared identity and a willingness to participate within this prescribed social order.

JS: Wow, you know actually that doesn't sound too dissimilar to a rock concert.

OF: Exactly. Exactly.

JS: Everyone gets together, becomes one mind, you know?

B: Mm-hmm.

OF: Yes. And you feel the power of something when it's given to you through music, much more so than if it's delivered just as a boring lecture, right?

JS: Right, absolutely. You could read a poem, or you could hear a lyric. People go around singing lyrics from songs all the time.

OF: Exactly.

B: Without even realising it sometimes.

OF: Yes, it goes into your soul. And especially if you have it at school. You know, the songs that we learn at school, they're the ones that you end up singing 30 years later. And then you realise “Oh my god, I was being indoctrinated.”

B: And you didn't even realise what the song was all about, until decades later.

JS: Those blasted ‘ABC’s, stuck in my head forever…

B: Yeah, and Confucius was so into it, and he had a great ability to appreciate music.

OF: You know, even back in the day of Confucius, he had such a lot to do with music. Where you look at Socrates and Aristotle and all the Western thinkers, and actually music wasn't such a big component of their thought back then. So there was something that Confucius himself thought of, much more so than was happening elsewhere. Which I just found fascinating. I mean, the guy was right.

B: And I think maybe it's something you said about how music hits the soul. Like it's at a level that's above logical thinking.

OF: Hm-mm.

B: Because I think a lot of Western ancient philosophers, they were really into logical discussions. But Chinese philosophy, I feel like it's at a different place. It seeks something that's more essential. I mean, even for Chinese people, we don't dare to study it, because it's so hard.

OF: Right.

B: So what led you to Chinese philosophy?

JS: It’s a good question.

B: What happened, Oscar?

OF: Does the phrase ‘midlife crisis’ mean anything to you?

B: Oh! Sure!

OF: No, no. I mean, what happened was, I'd basically been in Asia for 18 years, and I realised that I had a very superficial knowledge. And it wasn't just philosophy, I didn't know all the different dynasties, I didn't know anything. And in fact, the course I did, it was actually a Master's in Modern China studies, with a major in philosophy. So actually, it was a mixture of philosophy, history and literature.

JS: Mm-hm.

OF: So it was the perfect course. Buddhism and Confucianism and Daoism, these are things that I'd heard for two decades, but never really understood what the differences were. But look, in general, each philosophy appeals to different types of people. So it's extremely pragmatic. So for example, if you are someone who is looking to become a middle manager in your field, then Confucianism will appeal to you, because Confucianism is all about taking responsibility, how you manage your seniors and juniors, basically it's an intellectual pursuit. And then if Confucianism, for example, doesn't answer your question, then you can dip into another school.

B: Correct. Correct.

OF: So for example, Confucianism is not very heavy on how to manage peer relationships. So maybe that's when you dip into a bit of 老子 [Lǎozi]. And for example, it's not great on how to focus on mastering skills. So that's when you dip into 庄子 [Zhuāngzi]. It doesn’t say too much about how to be a leader or a sovereign: that’s when you dip into Legalism, for example. So it's not like Western philosophy, where you have one school that has to contradict the other school.

B: Right, right.

OF: That’s actually not what happened in Chinese philosophy, right? They can sort of layer on top of each other. And it's not about one being better than the other. It's like one showing you something which the other didn’t. Like, a lot of people in China, they have nothing to do with Buddhism, until they start thinking about their own death. And suddenly they think a lot about Buddhism.

B: Mmm.

OF: And it's the way that all of these different schools have kind of ‘syncretised’. That word means they've blended together in China - especially in modern China - where everyone can dip into whichever school they want, depending on what they need from it.

JS: Mmm. Well that’s really remarkable that you've had such a deep dive into Chinese culture, because you've been here a very long period of time. I had a question about Singapore. My wife is a huge fan of Singapore. And there are a lot of ties between China and Singapore. Can you tell us a little bit about what is similar and what is dissimilar about Singaporean culture versus Chinese culture?

OF: Hmm. Well, the obvious one is the speed of progress. I mean, Singapore only had its independence within our lifetimes - this is, like, in the last 50 years or so - And they've gone from a third world country to a first world country. I mean, that's very similar to what's happening in China right now. I would say Singapore is famous for its stable government, in fact they've had no changes of government. I think there's a similar focus on social order, that's for sure. They have a love of food. Oh my god, they are constantly eating.

BB: Mm-hm.

OF: So I think there are a lot of similarities. I guess the differences are also pretty obvious. I mean, the size. Singapore is just one city. And I think that allows it to experiment in this petri dish. Of course, China looks to Singapore and sees what they've done, and they’ve tried to take certain things and expand it to China.

JS: You've travelled around in China? Where have you been?

OF: Yes. I mean, especially these last few years, when none of us really could go anywhere else. So up to 黑龙江 [Hēilóngjiāng]; and then across to 甘肃 [Gānsù]; down to 云南 [Yúnnán]; 贵州 [Guìzhōu], another good place…

B: Was there like work involved? Or you were just like…

OF: Yeah, some of them were to do with the podcast. So it does allow you to see a city from a tourist angle, but then you get to know one layer underneath when you interview someone from that city. That's been great. A lot of tourism as well. Just when things get tough in your city, It’s always nice to try and find countryside, especially.

B: Right.

OF: When you live in an urban jungle like Beijing or Shanghai.

B: Can I go back to philosophy for a bit?

JS: Sure, absolutely!

B: I felt like I didn’t have enough of a dose..!

JS: More philosophy!

B: Maybe not about the philosophy in itself. But spending a year or two studying Chinese philosophy, did it help you to understand China better?

OF: I think it put into words the things that I had already noticed and experienced on a visceral level. It's about the way that China perceives the world; the way that the world perceives China; the prism which both sides are looking through, when they are trying to understand each other or purposefully not understanding each other. The language to really think about that in a deeper way, as opposed to just pulling my hair out as to the state of the world these days. I guess that's the way I would answer your question.

B: We’ll soon have no hair left.

OF: Yeah!

B: Seriously.

JS: Well, thank you so much for joining the show. Oscar.

B: Are we wrapping up now?

JS: We are wrapping up, Beibei.

B: Oh, OK.

OF: Thanks, Beibei. Thank you, Jason.