Season 01 Episode 12

Episode 12: The Refugee Researcher

Yael FARJUN - CEO, ChinaClickGo

Original Date of Release: 05 Nov 2019.

In 2010, Yael Farjun had a chance encounter with someone at the Shanghai Expo, which led her to undertake an amazing research project. We discuss the heroism and humanity of one Chinese man in Vienna, which resulted in an epic migration from Europe to Shanghai. And in so doing, we highlight Shanghai’s unique historical status as a Free Port, and a magnet for people from around the world.

You can also listen to catch-ups with Yael at the end of the interviews with Noxolo BHENGU from Season 02 Episode 14 and Ashley HUANG from Season 03 Episode 02.

To Join the Conversation and Follow The Graphics…

View the Facebook Album for this episode. Alternatively, follow Mosaic of China on WeChat.

To view the images below on a mobile device, rotate to landscape orientation to see the full image descriptions.

To Listen Here…

Click the ▷ button below:

To Listen/Subscribe Elsewhere…

1) Click the link to this episode on one of these well-known platforms:

2) Or on one of these China-based platforms:

To Read The Transcript…

[Trailer]

YF: And at that point, I became white. Completely. I was like “Oh, OK. Er, hi. Can you..? Do you want to come in?”

[Intro]

OF: Welcome to Mosaic of China, a podcast about people who are making their mark in China. I'm your host Oscar Fuchs.

Thanks to everyone who got in touch after last week's episode with Sebastien. The place where I received the most messages was actually LinkedIn, maybe unsurprisingly, since the content was more skewed towards corporate life in China. But quite a few of these were from people who I'd known for many years professionally without realising that they had children on the autism spectrum. So that was a real eye-opener, thanks again to Sebastian for sharing his experiences of autism in the workplace in China. And it was also another reminder about the interesting status of LinkedIn, which is the one mainstream social media platform which exists uncensored in China. Definitely something worth remembering for anyone out there who is trying to create bridges between these two worlds.

So on to today's episode, which is with Yael Farjun. I had met Yael before, but it was our mutual friend, Rebecca Kanthor, who told me about the specific story which Yael will be talking about today. So a big thanks to Bec. And apologies to Yael herself for the same reason, since I did feel bad about bringing her onto the podcast to talk about just this one thing, really. Because of this, I did make sure that we spent the first few minutes talking about other things. But then there's a handbrake turn into the main part of the story. You'll know it when you hear it.

[Part 1]

OF: Well, thank you Yael. I'm here with Yael Farjun. Yael is the founder of ChinaClickGo.com, which is a bespoke travel agency.

YF: Thank you for having me.

OF: And what is the object that you've bought that in some way describes your life here in China?

YF: So I brought the easiest one for me, it's my arm watch, my watch. Back in Israel, during army service and everything, you have to wear a watch because you want to know all the time where you're at. Then after the army service, I just decided “No, I'm going to get rid of my watch. And I'm going to live without it. Whatever, you know, spontaneously, whatever happens, I'll let the day lead me”. And I managed to keep it that way almost until I came to China. I think just at the beginning when I came to China, I realised “OK. No.” I had to get a bit more strict or organised and well-timed. So I bought a new watch. And ever since, that was my China thing.

OF: So is it a source of comfort, or a source of frustration, that you now have to wear a watch?

YF: I actually find it a source of comfort. Well, first of all, it's a jewel, right? It's sort of an accessory, so it's nice. But actually looking at my watch instead of my phone for the time makes it much nicer.

OF: Well, I've brought you in here for a specific story.

YF: Yeah.

OF: But before we go into it, let's hear about your background. So how did you first come to China?

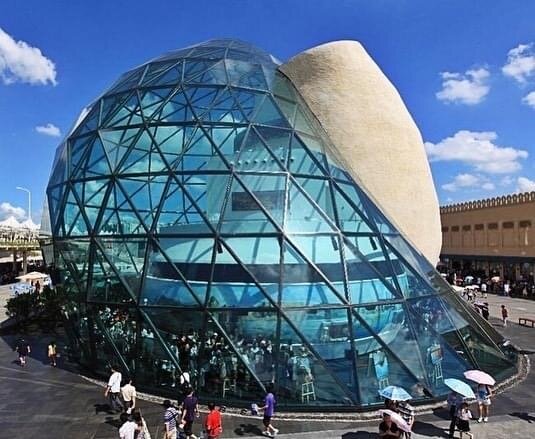

YF: I came to China first time in 2009 with a group of students. We all got a scholarship for studying Chinese, Mandarin Chinese. And that was my first ever trip to China. I came back to China a year after - it was even less than a year, in 2010 - for working at the Expo, the World Expo in Shanghai in 2010, Israeli Pavilion, and I was part of a delegation of… we were supposed to be the China experts, right? The people who could speak Chinese, and hence communicate with local crowds that came to visit the pavilion.

OF: Wow. Yeah, I came to China way after that, but I've heard stories about the Expo. Like, that was really when Shanghai opened itself up to the world for most people outside of China, right?

YF: Yes, exactly. It was the event of that decade, let's say, or something like that, that really made Shanghai change its face, knowing that we're going to have so many visitors, and they're going to be on the headlines of the news everywhere. So it was very important.

OF: And so after that experience then, you did end up staying in China, but what did you end up doing?

YF: So my first decision was that I want to stay. And then I had to figure out doing what. And I decided to start as a tour guide. It was the easiest for me to start with, I had a lot of knowledge from university, I love working with people, and I love travelling, I said “Why not?” Funnily enough, I never took a guided tour before. So I didn't have anything to compare it to. Like I knew “OK, I'm going to show people around, and tell them the history of places”. But then I realised it's so much more. The job of a tour guide is to open a door to a different, new culture. Really explain it, and really make it easier for those who are not from that culture to maybe feel connected with it. The challenges? Well, you're still working with people. And that always can bring challenges. I remember I think the biggest challenge for me was working with other people that, like me, never had a guided tour before. And it's not just language barriers, which of course exist around here, but let's say you have a health problem. And you don't think it's a big deal. And you've been travelling around the world before. And you managed, and everything is fine. And so you planned yourself a trip to Tiger Leaping Gorge. But then you realise that if you're gonna stay in the gorge during the night, you might not have electricity. Then what do you do with that thing you need to use overnight for your health? And people just, you know, it's not that easy to find out those small details about specific places where you travel. And that's why you need help organising your trip.

OF: It sounds like that's an actual example that you’re talking about.

YF: Oh my god, yes, it is an actual example. And as you can see, it was a traumatic one for me. Yeah, I ended up not sleeping the whole night, just so worried that my traveller will have a health issue during the night, and I won't be able to send someone to rescue them and get them to the nearest hospital.

OF: Right, because if you're doing that trek up the gorge, actually, you're nowhere near a city overnight, right? You're in the middle of nowhere.

YF: Exactly. It is literally in the middle of nowhere. And I think it's also a special area, where cars are not allowed in unless they belong to specific local villages. So you have to know someone from that village to be able to take you out, and of course pay them and the whole thing. And how do you even reach out to them, if they don't have electricity, and you have a problem at 1am or something like that? So yeah, that was a very stressful night.

OF: Well, this leads me to my next question, which is a little bit of a shift in tone. But you mentioned, of course, that you had done studies about China. But there's one specific area where you probably were just as surprised as I was when you heard about it, right?

YF: Yes, definitely. I think it was the first biggest surprise that I had in China. During that summer semester, the University arranged all sorts of activities for us in the afternoons. And one of them was going to visit the ‘Jewish church’. This is actually a synagogue in the 虹口 [Hóngkǒu] area in Shanghai. And that was the first time ever that I've heard that Shanghai has some historical background that has to do with Jewish people.

OF: Right, so where does that story start?

YF: Oh, wow. Well, it starts in the middle of the 19th century with the first wave of Jews that came to Shanghai as merchants, as businessmen. And later on others came, under completely different circumstances. Russian Jews, some of them refugees. And then, of course, the last big group of refugees that managed to escape from Europe just before the beginning of World War II.

OF: Right. So where were these particular Jews from?

YF: The majority of them came from Berlin and Vienna. Just because, you know, that's where people knew about the opportunity, the option of even coming to Shanghai, so they could tell others. The rumour didn't didn't make it to much smaller, much further away locations. It started in Vienna with one guy who went trying to get visas for himself and his family, to just get out of Germany. And he couldn't find anyone to give him those visas. And at some point, he found himself standing at the front of what used to be the Chinese Consulate. He wasn't sure it was the Chinese, he saw some weird characters and drawings and was like “OK, I guess it's somewhere from the east” but he wasn't sure exactly where it was. And he found himself standing there in line, waiting for his turn to go inside and ask for the visa. And by the time it was his turn to go inside, the consulate was already closing for that day. But he kept standing and waiting outside. And then a man came out, a tall gentleman according to the stories, and asked him “Sir, why are you still standing here?” And he said - Eric Goldstaub, that was the man's name - and he said “Well you know, we are trying to get visas for me and my family. I have three children. We need to get out of Germany, and no-one will give me any visas”. And so the man - now we know it was Dr. 何凤山 [Hé Fèngshān], Consul General of China in Vienna, Austria, at that time - he said “Well, give me your passports if you have them, and let me see what I can do”. And he took the passports, and the story goes that he didn't sleep for the entire night trying to figure out a way of making this happen. Because he couldn't issue a refugee visa, that was an order that he could not violate. But he really wanted to help. At some point, he came up with a solution, realising that if he issues a visa specifically to Shanghai, it will help the Jews get out of Vienna, and enter into China. Because Shanghai was an open port, you didn't need anything coming in, you didn't need to show any papers. So he realised that this is where he has strength, and that's what he can do to really help. And he started issuing those visas, specifically to Shanghai.

OF: And so, do you have any idea about how many people went through the same process?

YF: So this is the thing, we are not exactly sure how many received Dr. 何凤山 [Hé Fèngshān]'s visas. His daughter, who is researching his life work - she lives in the U.S. - she found records of about 4,000 visas. But we know of about approximately 15,000 Jews who managed to escape Berlin, Vienna, up until even 1941, which is already way into the war, but managed to escape and come all the way to China.

OF: And so what was that journey like? What was the way that they came?

YF: The majority of the people took trains to Italy, and from there took cruise ships, all the way to Shanghai. it could have taken between two to four weeks at sea, depends on how many stops they had on the way. And you can actually see on their passports, like, the different chops of wherever if they went offshore. So you can see different stamps from different places.

OF: Wow, so they would have had to have bought those cruise tickets. So that wouldn't have been very cheap.

YF: Definitely not. And many of them either sold whatever they could, or took all their savings. Loans sometimes, from family and friends. One of the things that they did was to buy much more expensive tickets, and then downgrade themselves when they got to the ship, so that they will have some cash with them when they arrive in China.

OF: What life did they encounter, then, once they arrived in Shanghai?

YF: Well, completely different than what they knew back home, of course. Not just the climate that was different, but they couldn't bring much with them, they couldn't sell much of what they had. So they came here with nothing, technically, and they started very much at the bottom.

OF: What then was your personal connection with this? So I mean, this is back in 2009, when you first heard about it. So how does your personal story progress?

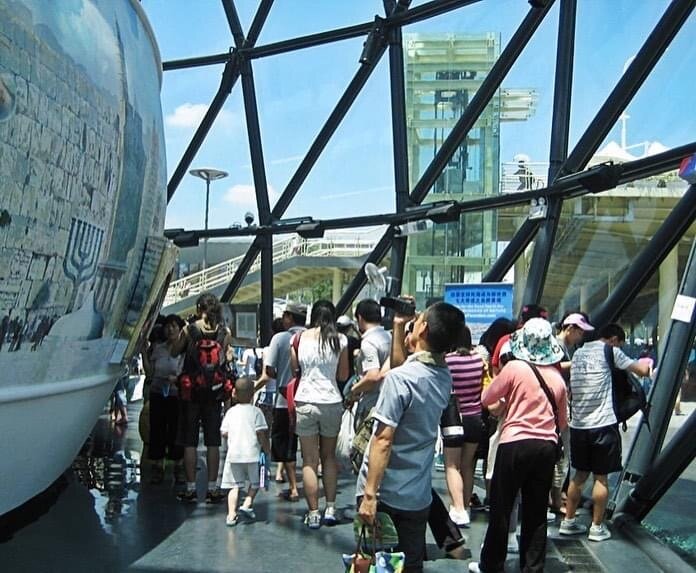

YF: So when I heard it the first time, first of all I was shocked. I was like “How come I've never heard of anything like that before. I'm Israeli, we learn a lot about the Holocaust, we learn a lot about, of course, Jewish history around the world. And they had a full bachelor degree about China. And no-one never mentioned any Jewish connection. So that was one thing that kept me really up at night in a way, you could say. I tried to read as much as I could after that visit, found out whatever books I could, whatever articles, and really tried to get more knowledgeable about it. And then in 2010, when I came back to work at the Expo, we used to have about 300 people every 15 minutes coming into the pavilion. And so the line, you know, started building up outside the door. And once in a while we'll have those who are trying to cut the line, of course. And, you know, we got kind of got used to them at some point. Then one day I was sending up the entrance, and one of the first things that people would see when they came in was a sign that the Foreign Ministry of Israel put there, it was the first thing that anyone who came into the pavilion saw, with a picture of Dr. 何凤山 [Hé Fèngshān] and the story of what he did, and how he saved so many Jews. And so an elderly guy was standing at the entrance, and kind of like pointing at the sign. And I was looking at him, and I thought he wants to cut the line. And so I looked at him and I actually approached him in English. I don't know why not in Chinese because he looked Chinese and I was like "Yes sir, how can I help you?” And he looked at me and he said “Well, this is my father”. And it didn't sink in at the beginning, what he said. I really, honestly I thought he's just trying to cut the line and get into the pavilion. It was a very hot day, and I could totally understand, you know, and feel for him. And I started telling him “Yes, this is Dr. 何凤山 [Hé Fèngshān]”, you know, I'm kind of like telling him the story. And then he looks at me and he says “Yes, I know. I'm the son of Dr. 何凤山 [Hé Fèngshān]. This is my father”. And at that point, I became white. Completely. I was like “Oh, OK. Er, hi. Can you..? Do you want to come in?” And we got him in inside the pavilion, and he was walking around with his wife, and accompanied by a Chinese student. Because when he left China he was about eight or nine years old. And they spoke a little bit of Shanghainese at home, but he couldn't speak Mandarin.

OF: Oh so wait, so he actually was from America at this point?

YF: Yes. Yes. So when he replied, he replied in, you know, perfect English. And so we continued the conversation in English. And then he walked in with his wife, and this student that was helping to translate. And we got to meet and we asked him “Why didn't you say you were coming?” You know, as Israelis in Shanghai, and the Jewish community, and the consulate will probably want to celebrate, and do something to honour him. And he said something that stayed with me, and you know, really, I will never forget. He said “I didn't think anyone remembers. I didn't think anyone will care”. And that's why he didn't even bother telling us that he's coming. And I remember how I felt bad about this. How come the son of someone who did such an amazing thing for my people, and we're not even acknowledging it or not acknowledging enough? And that was a moment for me that I will never forget, thinking afterwards that I need to do something about it. So I tried to find a way to collect as much information as possible, to create sort of a library of that information, and make it public so more people would be able to learn and research and understand that part of history that not a lot of us had heard of. And part of the thing that I did, in 2014, I had a chance to travel to the U.S., actually on behalf of the Ohel Moshe synagogue - today's Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum - to interview former Shanghai Jewish refugees. And I went, joining them on a cruise ship. The theme was ‘taking the cruise in memory of their parents, who took them on the cruise that saved their lives’.

OF: Right.

YF: And I had an incredible opportunity of meeting eight of them: two of them in their 90s; I think three or four were in their 80s; and the rest in their 70s. And I just asked all of them, would you mind being interviewed to the camera and telling your stories? Whatever it is that you remember? And that was a profound experience for me. That was incredible.

OF: Wow, what happened to the refugees after the war? Did did most of them go back to Europe and the States?

YF: Yeah, eventually. In the States, so the largest group that we know of former refugees to Shanghai lives in the States today. The second largest group is actually in Australia. And then the third is in Israel. Some went back to Europe, mostly to Vienna, but then the majority didn't stay there.

OF: And so, when you did these interviews then, can you remember any specific stories that that stand out?

YF: So one of the interesting things that each and every one of them remembered was that their parents tried very hard to make sure that the children don't suffer, or acknowledge, or be aware of the hardships. In a way that, well, they had lots of professors and musicians, and even an Olympic boxer. They had ballet dancers, they had theatre actors. And so they tried to fill in the time with activities, cultural activities, from back home. And the kids were allowed to participate in almost everything. And so it was very important for the parents that the kids would continue their education, and connect to the culture that they came from. And so they actually said that there were so many activities, and things to do, that there are days were never dull, they were never boring. They had Sunday schools. They learned Hebrew, they learned English. They really made use of whatever resource they had. And regardless of the circumstances of what happened around them.

OF: And you talk about the circumstances, so how did the situation change once war came here to China?

YF: So to be fair, we need to remember that the Japanese were surrounding Shanghai already in 1932. So, many years before the war in Europe even broke out. The big change happened in 1941 when Japan actually joined Nazi Germany. And then everything changed in Shanghai, because if you were of the wrong nationality, then you became an enemy of Japan. And that included Americans and British and others that were here, that in Europe were enemies of Germany automatically became enemies of Japan here. That meant a lot for the Jewish communities that lived in Shanghai at that time. For all of those who were British - and among the older Jewish community, the Sephardic Jewish community that was here, many were British citizens - so they were put in prisoners of war camps. And their lives, of course, changed completely. The second group was the Russian Jews, they were actually the ones that suffered the least, because there were still Russians, and Japan didn't want to mess up with Russia that much. But the third group, our refugees who came from Europe, there were stateless. So technically, they had no nationality. But of course, the Nazis recognised them as part of the Third Reich, or they knew where they came from. So they started demanding the Japanese to ‘deal with them’, let's say it this way. There were all sorts of plans, some of them to completely kill all of the Jews that were here; others to put them in different types of camps. It ended up with the Japanese agreeing to put them in a designated area, which was that area in 虹口 [Hóngkǒu] where the majority of them already lived. And technically that changed the lives of everyone living in Shanghai. Not just the Jews, by the way, but yes.

OF: Yeah, of course. And this is where it all goes into context with everyone else's hardships. But Isn't it ironic that actually, the Jews were first saved by Dr. 何 [Hé] in Vienna, and then here, they were saved by the Japanese?

YF: In a way, yes, it is.

OF: And so what is the status now then? Here we are in Shanghai, you mentioned that there is this Jewish refugee museum? Is it known among the Shanghainese people about this story, or in China in general?

YF: I think there is a greater awareness of it today than it was when I came here, that's for sure. The museum is doing a really good job at archiving and collecting materials and stories. I think that because of their really good job, more and more people are aware. Shanghainese for sure are aware of this. They grew up with, you know, those stories. So they know that much better than those who are coming in from other places. But the story gets more and more attention, let's say, being taught a bit more, being shared a bit more definitely in recent years than than it was before.

OF: Well, as you say, it's one part of a very big story when it comes to what happened in those times.

YF: Sure.

OF: But because it's such an interesting connection that most people don't know, especially where we heard about the Oskar Schindler story in Germany, and to have an equivalent here in Shanghai, which no-one knows about was was a real eye-opener. And I agree with you that the museum does a great job, and the volunteers there - who are Shanghainese mainly, right - they’re really passionate. I was really impressed with how much knowledge they had, and how they wanted to give up their spare time to tell others.

YF: True. Many of them are volunteers.

OF: Well, thank you Yael. I really appreciate that.

YF: Thank you.

OF: And let's move on now to Part 2.

YF: OK.

[Part 2]

OF: Now Part 2, there were 10 questions. So I hope that you're ready.

YF: OK.

OF: Number 1, what is your favourite China-related fact?

YF: OK, so you know how people claim that you can see the Great Wall from the moon? That is not true.

OF: Right. Right. I wonder how that rumour got started?

YF: Yeah, that that would be interesting research.

OF: Do you have a favourite word or phrase in Chinese?

YF: Oh, definitely. 哎哟 [Āiyō].

OF: 哎哟 [Āiyō].

YF: I don't even notice that I’m using it, you know, it's so natural for me now.

OF: And it's like “Oh my God” or, how would you describe it?

YF: Yeah, something like “Oh, gosh” or something like that.

OF: Yeah, usually out of frustration, isn't it?

YF: Yes.

OF: What is your favourite destination within China?

YF: I've been to 阳朔 [Yángshuò] a few times, I have good friends there. And I just cannot have enough of that place. It's just… it's magical.

OF: Right. That's the area where there's the mountains jutting up straight from the water.

YF: Exactly.

OF: Amazing. If you left China, what would you miss the most and what would you miss the least?

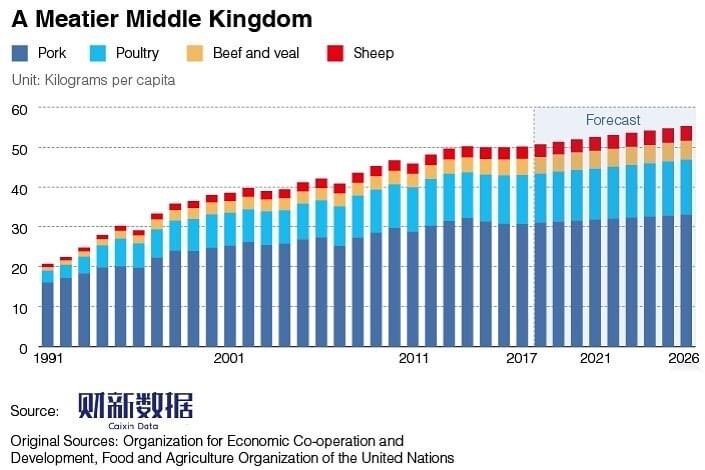

YF: Miss the most will be how easy things can be here in terms of ordering things online, let's say. Or the fact that you can just walk out of the house with your phone, and you'll have everything at the tip of your fingers. It's really… Sometimes going back home feels like going back in time. But that's definitely… We've been spoiled here. Miss the least would be… I love Chinese food, and unfortunately most of it is made with pork. So yeah, which is a problem for me. So miss the least is the fact that even when you ask in restaurants “Please don't put pork, nothing with pork”, they would still shred a little bit of pork on top of it, because “What do you mean, you cannot have it with pork? But this is the whole flavour of the thing!” Yeah.

OF: Oh god, it's so true. It's ubiquitous.

YF: Yes.

OF: And, like, there'll be a salad. And of course, just…

YF: A little bit of pork on top of it. That's what, you know, gives it the taste.

OF: Yes. Oh, funny. Is there anything that still surprises you about life in China?

YF: Yes, I think again, how fast things happen here. How a decision is made here, or a direction is chosen, and things just start racing in that direction. And it's just incredible how there are new things happening in China almost on a daily basis. And they happen fast. They happen big. Yes, I think that's still surprising.

OF: What is the best or worst purchase you have made in China?

YF: Well, I can definitely say my best purchase was my 小米 [Xiǎomǐ]. I love this phone. It's an extension of my hand, and my life is within my 小米 [Xiǎomǐ], really.

OF: And 小米 [Xiǎomǐ] was famous because they have two SIM cards, right?

YF: Oh yes, two SIM cards, a really easy plan for roaming services outside of China. I don't even change my SIM card anymore. I just buy it on the phone.

OF: What is your favourite WeChat? sticker?

YF: So I sent you the sticker…

OF: Oh, yes.

YF: …Of Gal Gadot, when she is excited about something, I find myself using that a lot in China, because again, there are so many new things happening all the time, you know. And so I'm excited a lot about daily life in China. And, well it's Gal Gadot, so of course, you know.

OF: What is your go-to song to sing at KTV?

YF: The only song that I actually know the lyrics of - it’s a pretty old song - is ‘Killing Me Softly’. That's the only song that I actually remember all the lyrics to. And for some reason they have it in KTV. I try to avoid KTV, to be honest, as much as I can. But if I do go, and I'm forced to sing, then this is the song that I probably will choose.

OF: Very nice. And finally, what other China-related media or sources of information do you rely on?

YF: Mostly my WeChat, to be honest. So WeChat feed articles, I'm following quite a lot of official accounts. And we have different groups of people sharing different sectors, like industry sectors, or segments of the economy type of articles. Very, very interesting. And the easiest, the most useful, and relevant, I would say. Because it's just… again, it's just easy.

OF: Well, thank you very much, Yael.

YF: Thank you so much for having me.

OF: And the final question before you leave is, out of everyone who you know in China, who would you recommend that I interview next?

YF: OK, so I had a pretty long list to be honest, but I had to narrow it down. And I chose to recommend Charlene Lee, who is Co-founder of ‘Ladies Who Tech’ a community of women, to encourage women to get more into tech. So I think that what she's doing is very important and really inspiring. And plus, she's a really cool person. So that's my recommendation.

OF: Well, great. I look forward to speaking with Charlene.

YF: Great.

OF: And I really enjoyed our chat today, thank you again.

YF: Thank you.

[Outro]

OF: So there are a few interesting photos on social media accompanying this episode. As usual, please find them on @oscology* on Instagram and @mosaicofchina on Facebook, or add me on my Wechat ID: mosaicofchina* and I'll add you to the group there. We start with the photo of Yael and her object, which was her wristwatch. Her favourite which sticker is there too, the one with the excited Gal Gadot. There is a chart showing how much pork is eaten in China versus other meats. You can see clearly how difficult it is to avoid pork in this country. And then there are some photos of 阳朔 [Yángshuò], Yael's favourite destination within China.

The other ones need a little more explaining. First, there are some from the Israel Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo. Then there's one of 何凤山 [Hé Fèngshān] himself. Then the next three are all from Yael's research. The first one is Yael interviewing a local Shanghainese lady who was a childhood friend of a former refugee. And then this is followed by another photo of Yael standing in front of the Jewish Refugees Museum with a man who was born in Shanghai to a refugee family, and lived here until the age of about 10. And the final picture is an interview Yael did with a 94 year old Jewish lady in New York, whose house in the U.S. is still filled with furniture and pictures, and other artefacts that she and her husband brought back from China after the war. Mosaic of China is me Oscar Fuchs, extra editing support from Milo de Prieto, artwork by Denny Newell, and China support from Alston Gong. Thanks for listening, and see you next week.

*Different WeChat and Instagram handles were mentioned in the original recording. These IDs are now obsolete, and the updated details have been substituted.