Season 01 Episode 09

Episode 09: The Workplace Documentarian

Noah SHELDON - Photographer and Filmmaker

Original Date of Release: 08 Oct 2019.

This week’s episode is with Noah Sheldon, who has been taking photos and making films of workers in China over the last decade or so. We discuss some of the factory conditions that aren’t covered in much of the world’s reporting on the issue. We talk about the condition of the average migrant worker in China. And we focus in on the lives of one or two people that Noah has encountered as part of his work.

To see some of the work mentioned in our conversation, see www.noahsheldon.com.

To Join the Conversation and Follow The Graphics…

View the Facebook Album for this episode. Alternatively, follow Mosaic of China on WeChat.

To view the images below on a mobile device, rotate to landscape orientation to see the full image descriptions.

To Listen Here…

Click the ▷ button below:

To Listen/Subscribe Elsewhere…

1) Click the link to this episode on one of these well-known platforms:

2) Or on one of these China-based platforms:

To Read The Transcript…

[Trailer]

NS: For me, he was a proxy for Trump. I mean, all these films are like proxies for someone else, right?

OF: Ah yeah.

NS: So for me, he was like this perfect kind of Trumpian figure. It's so interesting to see the Chinese version of Trump.

OF: Yes.

[Intro]

OF: Welcome to Mosaic of China, a podcast about people who are making their mark in China. I'm your host, Oscar Fuchs.

So in last week's episode with Vy, we discussed that the population of Shanghai was the same as the entire population of Australia. Well in fact, as my friend Alston in Chengdu pointed out, this comparison was based around the number of people who have the official residency - or the 户口 [hùkǒu] - in Shanghai. So let me be clearer, the population of Australia is estimated at around 25 million, the population of Shanghai that have the 户口 [hùkǒu] is around 24 million. But in terms of the total population of Shanghai, which includes people without the official residency, it's anyone's guess. By some estimates it could be as much as 35 million people. If you're interested in learning more, just search for ‘The Hukou System,’ and you can find out more about it online.

The reason I mention this in particular ahead of today's episode, is because we talk a lot about migrant workers in this conversation. This week, I'm talking with Noah Sheldon, who has been making photos and films of workers in China over the last decade or so. We discuss some of the factory conditions that aren't covered in much of the world's reporting on the issue. And we focus in on the lives of one or two examples of the people Noah has encountered as part of his work. I first met Noah at the leaving party of a friend of mine who worked in supply chain. And Noah was there because he was an official photographer for this company. I was curious to understand what that meant, and what kind of photos he took, and this is what ultimately led to the today's episode. The company in question is a big fan of the nondisclosure agreement - and you'll hear Noah mention ‘NDA,’ the acronym for this, in our conversation - and it's the same reason why you won't hear him mention the name of the company itself. The other two useful things to know is that the word 老板 [lǎobǎn] simply means ‘boss,’ and the word 差不多 [chàbùduō] means ‘more or less’ or ‘not far off’.

And one more thing, I've purposefully edited down our conversation a little shorter than other episodes in this series. This is because I want you to have no excuse to spend four minutes watching one of the short films that Noah mentions in our chat. So when you hear us start to talk about this, pause the podcast, go to noahsheldon.com. Find a series called ‘Work is’ and scroll down to find the film in question, you can't miss it. And I'm not exaggerating, it’s only four minutes long; it will give an extra context to this conversation; and it's a beautiful piece of work.

[Part 1]

OF: I'm here with Noah Sheldon, photographer and filmmaker. And welcome to Mosaic of China.

NS: Thank you.

OF: So what object have you brought today?

NS: I brought a camera because that's a lot of what my relationship to China has been. It gets me out of house, it gives me something to do. The first time I came to China was in 2003. I was working on an annual report for United Technologies, this huge conglomerate. The subway system in Shanghai was brand new, and I was here to photograph the escalators and elevators for Otis, which United owns.

OF: Right.

NS: So I was here doing that. And it was my first time in Shanghai. The Bund was very different, a lot of things were very different. I took a lot of pictures out of my hotel room. Then when we moved to Shanghai in 2010, nothing was the same. It was amazing. It was like there were maybe two buildings standing, from the panorama from outside my window, still standing. We only lived a block away from the hotel I stayed at in 2003, which was very funny.

OF: And do they still have the Otis escalators in the metro?

NS: They do, they do. Yeah, so I was there for that. Also some kind of hydraulic pump factory, which I loved. That was a small factory - that was in 2003, same trip - it was like some company they owned. And they had a little DJ booth, and they had a system where they had a schedule of what worker got to choose the music that they play in this factory.

OF: You've probably gone to quite a few factories in your time.

NS: Yes, yeah. So one of the things that brought me here - even before I lived here - was, I do a lot of work with a large technology company. And for them, I was involved for a number of years in terms of their responsibility towards their workers, and their supply chain, and the environment. And so through that I probably visited over 100 factories. Tiny little suppliers, to huge, huge factories with hundreds of thousands of workers, the size of cities. And yeah, it's been fascinating, it's been a really interesting glimpse into a different side of China than a lot of people see. And one of the things I've gotten to do is, I've gotten to do a lot of interviews with workers, trying to figure out how they can make things better in those situations. We have this way of projecting - when reading a story about a factory in China - that our consumption makes these people slaves, or something like that.

OF: And that’s a preconceived idea before we even go to the factory, right?

NS: I think so. I think so, yeah. And then, when you go to a factory, there’s so many interesting factors, that really don't get covered in the press. The biggest thing I would say, is the whole kind of idea of being a migrant worker in your own country. And this idea that we have, you know, in China there’s 300 million or 400 million - whatever the crazy number that I keep hearing is - migrant workers in their own country. And that's kind of given as background in all our stories. But when you actually think about what that means, it's a really interesting condition. And when you talk to workers, that tends to be one of the big ones. It's either young workers, where it's exciting to be away from their home, their farm or whatever; and older ones who have families and have kids, and that tends to be something that's very hard for them. So, you don't realise how temporary these jobs tend to be for a lot of workers. And the reporting never reflects that. We think of people having these as lifelong careers, and that tends to not be the case.

OF: Right.

NS: I think for a lot of people, it's like a first job. You know, the worker that’s going to factories has changed so much, obviously. Even 10 years ago, there were a lot of farm workers who were happy to be inside. And they would work seasonally, when there was no work to be done on the farm, stuff like that. And now young people obviously expect a lot more. And for them, it's like “Well, I'm working in a factory, but what I ultimately want to do is I want to open up a hair salon back in my village,” or something like that. And that's been really interesting to see that shift. It's like a university for kids who will never get to go to university, right? Like the entire factory, hundreds of thousands of people, are 18 to 25. And, some of them, it's very funny, once the sun goes down, there’s this park benches everywhere, you see all these young couples holding hands. It's very sweet. It's interesting, yeah.

OF: In all of your experience with workers, are there any specific stories that that jump out? Any particular people that stay in your memory?

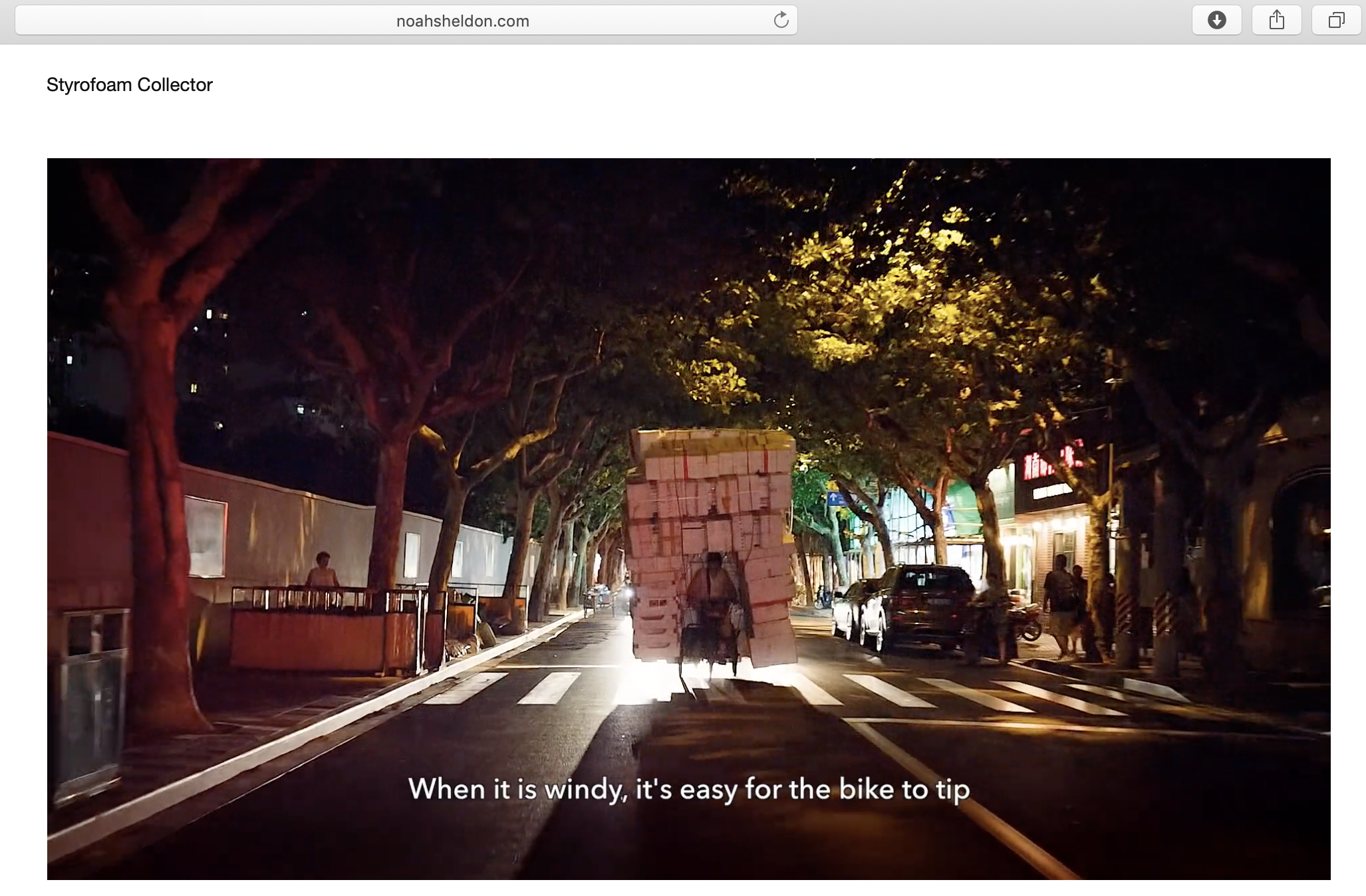

NS: Just a couple years ago, I started a series of films, based on the company I do a lot of work for. I'm bound by a lot of NDAs. So I thought it would be so great to be able to give context to these stories, without breaking those NDAs. So I found almost like proxy stories. So if the issue is being a migrant worker, being away from your children, I thought it'd be so great to find someone who has a similar situation. And that not hard in China, right? So I did a film about a woman who’s a styrofoam box recycler. So much of her life is living away from her kid. And there’s this heartbreaking part of the movie where she talks about, she hasn't been home. The longest she went without going home is three years. And when she went back, her kid didn't recognise her, wouldn’t call her “mom”. And I think that condition of being, you know… I went to her village. I tried to get her to come with me, but she didn't want to go, she didn’t want to skip work. And so I went, and it's only… it’s not even a 3-hour train trip. It was really… I think it's shorter. And so yeah, it's heartbreaking to kind of imagine that condition, where you're so close to home, but you can't go there.

OF: And did you show her the final video?

NS: Yeah, I did. Like, she still couldn’t figure out why I made a film about her. She was like “Yeah, this is just normal”.

OF: And so was that film released in China? Like, what was the the feedback?

NS: It's mostly been out of China. It's been in a bunch of film festivals, and had a really nice response from people. But I've also gotten a nice response here. Yeah, people are pretty amazed to see her story. And what most Chinese tell me is, they see these people all the time, and they would never think to ask them that story.

OF: Right.

NS: Yeah, a huge inspiration for me is… I don't know if you know the work of Studs Terkel?

OF: No.

NS: Studs Terkel was a great Chicago journalist. He did a great series of interviews on work, where he just asked normal people about their job. You know, it's something that we do most of our time, and yet we don’t talk about it that much.

OF: I think you can look at people, you can objectify them. But as soon as you get their story, then obviously you can empathise with them, right?

NS: Right, right. That's key, you’re right.

OF: There was another work project that I know that you were involved in. And that was that documentary you did about the hairdressing school, right?

NS: Yeah. Yeah. So I've been really interested in a range of jobs, and a range of personalities, right? So I've spent time with the guys who scalp mooncake tickets, the guy who owns a fireworks factory, a Sichuan opera singer. There's a lot. A Taobao model, like a fast fashion e-commerce model, she was great. Yeah, quite a few different topics. And I have this list of 100 occupations or locations I would love to film. And one of them has always been this figure of a 老板 [lǎobǎn], like this big boss guy. And there's this incredible hair school called 文峰 [Wénfēng], where this guy has kind of modelled himself as this cult of personality. And he runs this kind of very militaristic school of hairdressing, and makeup, and different beautician processes. And so I was fascinated by this guy, walked past his salon every day. He has salons all over China. And he trains thousands of hairdressers. For me, he was a proxy for Trump. I mean, all these films are like proxies for someone else, right?

OF: Ah yeah.

NS: So for me, he was like this perfect kind of Trumpian figure. It's so interesting to see the Chinese version of Trump.

OF: Yes. Because he created his own reality in that place. And obviously, you know, you can look at it as an outsider and go “What? How does that work?” But as an insider, of course, you ‘drink the Kool-Aid’.

NS: Right. Exactly, exactly. And I don't know. I mean, some of the employees we talked to are definitely drinking the Kool-Aid. They fully believe his crazy claims. Others, we get the sense that they're just in it for the way they can get commissions.

OF: Right.

NS: It was interesting. It really is a huge community, so there's definitely a spectrum in that community.

OF: Yeah. And it looks like then, you're moving away from photography, and more towards filmmaking. Is that true?

NS: I do a fair share. And the world seems to be moving more towards motion, in general. I think with 5G internet, things are gonna change very drastically. So I just want to bring it back to the camera. So when I came to China, when we moved here, we moved for my wife's work. And I was doing quite a bit of work here, but I was also doing quite a bit of work everywhere. And I was travelling to Europe a lot, I was travelling all over the place. And so when I got here, I started a blog, like a photo-a-day blog. My daughter was 1 at the time. So I would kind of wander around with her, but I would always bring the camera, just as a way of interacting with the world around me. I quickly printed some cards, like I had my friend write in Chinese, like “I'm a photographer, I'd like to take your picture, can I take your picture?”

OF: Nice.

NS: And so I'd walk up to people, and hand them the card. And my daughter was great. I'd bring my daughter, and they would see a baby, and that was a great icebreaker. And I realised there wasn't a lot of kind of normal… You know, when you Googled pictures of China at that time, you'd see pictures of pandas, or the Great Wall, or something like that. And I really appreciated that interaction, I really appreciated making this archive or someone. The thing that brought me to photography in the first place was, when my mom passed away, I was 15, and she had made these little family photo albums, crappy family photo albums that she had thrown together. And when she passed away, I couldn't really talk to people. She’d been sick for a while, and passed away. And so I would spend a lot of time looking through these family photo albums. And I was just amazed at what these photos had become overnight. You know, they went from being these crappy snapshots, to being these really weighty documents. And for me, that transformation was just fascinating. It was kind of scary, but also really, incredibly powerful. And the idea of documenting everything became really comfortable to me. And so I started doing that, I started getting more and more interested in photography. And so for me, so much of what photography and filmmaking is, is documenting something that won't be here, right? So when I got here, I realised no-one was telling those stories, I couldn't find them. And I think even, the thing that would happen to me most often - especially when I first got here, when I was really just taking pictures all the time, of everything - was old people, young people, all kinds of people would walk up to me and say “Why are you taking a picture of this building? Go take a picture of that new building”. You know, “This buildings is old, it's gonna be torn down, it’s blah blah blah”. And I thought that was so interesting, a place without nostalgia. And I think that's a big part of China, is that change has been so rapid. The Cultural Revolution did so much to kind of erase so much.

OF: Well, thanks so much. We covered a lot of ground there. Really appreciate that. And now on to Part 2.

[Part 2]

OF: OK, so the first question is, what is your favourite China-related fact?

NS: Let's see, so according to Wikipedia - which I just looked up - there was 287 million rural migrant workers in China in 2017.

OF: Wow.

NS: Which I think is amazing, to be migrant workers in your own country. I think that's a really interesting kind of policy, because of the residency permits and stuff like that.

OF: Yeah because there could be equivalents in other countries, but they don't track it in the same way, right?

NS: You know, this is a way of controlling things like urban slums and stuff, right? They keep people tied to the countryside. Which is a really interesting policy. And I have to say, it’s managed growth in an interesting way. There's obviously negative fallout from it, but yeah, it's fascinating.

OF: Do you have a favourite word or phrase in Chinese?

NS: I have a least favourite, 差不多 [chàbùduō].

OF: Ah, 差不多 [chàbùduō]?

NS: I absolutely despise that.

OF: Really? Oh that's actually one of my favourites.

NS: In terms of working and stuff, and if you're really going for excellence, it's this really dangerous kind of idea of ’It's good enough’.

OF: Right. Yes, I mean, there is a time for 差不多 [chàbùduō] and there’s a time for “No, get it right”.

NS: Right.

OF: And obviously, in your line of work, there’s more perfectionism than a 差不多 [chàbùduō].

NS: Yeah. But you're right, you’re right. There is a very positive side of it. It's just… yeah.

OF: When you don't want to hear it, it’s the last thing you wanna hear.

NS: Exactly, exactly.

OF: What's your favourite destination within China?

NS: You know, I've been to the Tibetan autonomous area, and 四川 [Sìchuān], I think that's amazing, rural 四川 [Sìchuān] is amazing. I love Shanghai, Shanghai is such a beautiful, amazing city. But I always love getting out of Shanghai as well, because it's like…

OF: Yeah.

NS: You don't have to go far. You go an hour outside of Shanghai, and all of a sudden you're in this very different place. Yeah.

OF: Well, yeah. Rural 四川 [Sìchuān] is on my list, so thank you. If you left China, what would you miss the most, and what would you miss the least?

NS: I love the public life here. I love seeing things on the street, I love seeing life lived out on the on the street. I live in a lane house, I love hearing the neighbours. When we go visit my dad in Chicago, my daughters instantly are kind of freaked out about how quiet it is there. Yeah, I love the optimism here. I love seeing kind of, you know, you have this huge percentage of the population - I think at this point, probably everyone - who have only seen progress, right? And that's amazing. It's very different than when you go back to the U.S. or somewhere else, where people are much more sceptical.

OF: And is there anything that still mystifies you about life in China?

NS: Yeah, how things can be 差不多 [chàbùduō] and that’s OK. Sorry.

OF: Oh, 差不多 [chàbùduō] again.

NS: Yeah, I mean, that just really… I can't get over that. Like to me, that’s just so… That sounds so bad, because obviously people are doing amazing things here, and people strive. But I do think it's kind of like, I don't know, it holds a lot of things back.

OF: Right. What is your favourite place, to eat or to drink or generally to hang out in Shanghai? Or elsewhere?

NS: There's a restaurant we love. What is the name in Chinese? The English name is ‘In & Out’. It's a horrible translation.

OF: In-N-Out Burger?

NS: No, no. ‘In & Out’, it’s a 云南 [Yúnnán] restaurant.

OF: Oh right.

NS: And it’s in 湖滨道 [Húbīndào] mall. And it's so excellent.

OF: I know it, it's on the third floor, yes.

NS: Exactly. I think the food there is so great. But they don't have a lot of alcohol. So that's kind of a problem.

OF: OK. What's your favourite WeChat? sticker?

NS: Mmm. There's one that I've been very fond of lately, which is a girl on a bicycle chasing a motorcycle.

OF: And in what context do you use that, like when you're running late? Or…

NS: More like doing something impossible. Like ‘we can do it’. I'm also very fond of the the boy with the extremely large comb, slowly combing his hair.

OF: Yes. That's a very good one. Actually, if you look at both those stickers, there's no 差不多 [chàbùduō] about either of them.

NS: No.

OF: So that's probably why you like them.

NS: They're fully fully…

OF: What is your go-to song at KTV?

NS: My favourite KTV song is, if you want get everyone going, you can always do Tiny Dancer.

OF: Very good.

NS: I think that’s…

OF: That’s a classic.

NS: Everyone loves that.

OF: And finally, what other China-related media or sources of information do you most rely on?

NS: I find, you know, people like Bill Bishop - the old Sinocism blog - I find them pretty amazing. A book I want to reference that I'm obsessed with is called The Corpse Walker, by 廖亦武 [Liào Yìwǔ]. And that's an amazing book, he kind of is the Studs Terkel of China.

OF: Well, thank you so much for your time Noah, it was fascinating. And before you leave tell me, if there was one person who you'd recommend that I should interview next, who would it be?

NS: There are people doing really interesting things here. I think the people at the Rong Design Library are fascinating. They're doing such an important thing in creating such an incredible archive, Jovana and her husband Lei. They have created this incredible archive of Chinese design, both traditional and folklore, and more modern stuff. And it's absolutely phenomenal.

OF: Awesome, I look forward to meeting Jovana. Thanks so much, Noah.

NS: Great, thank you. That was fun.

[Outro]

OF: So that was the smooth and relaxing voice of Noah Sheldon. I probably should have warned you about that at the beginning of the recording. This is probably an episode for listening to when relaxing on a sofa, by a crackling fire. I take no responsibility if you were listening to it while driving late at night on a dark country road, or operating heavy machinery.

Once again, to see Noah's work, go to noahsheldon.com, and look under the heading ‘Work is’. You'll also be able to see details on his site about where you can see the film about the boss - the 老板 [lǎobǎn] - of that chain of beauty schools. The title of that film is ‘The School of Beauty and Long Life’. Since this interview was recorded, actually Netflix has released a great documentary movie called American Factory, where you can see another Chinese 老板 [lǎobǎn], this time of a glass company, and it focuses on what happens when a similar kind of traditional Chinese factory culture gets exported to suburban Ohio. The film does focus on the predictable clash of cultures, but I thought it was quite an even-handed attempt at showing the pros and cons of both working cultures.

As for connections between Noah's episode and other guests in this series, Noah was the second person to mention Bill Bishop's ‘Sinocism’ as one of his favourite sources of information about China. The other person was Eric Olander back in Episode 03, and I definitely also recommend you get on his mailing list. Thanks very much to everyone who is following the podcast on social media, I really appreciate all of your contributions. I forgot to take a selfie with Noah at this time, but there are still lots of interesting images from this week's episode. There's Noah with his object, his camera of course; the phrase 差不多 [chàbùduō], meaning ‘more or less’ or 'not far off’ that terrorises Noah's life; his favourite WeChat stickers; his favourite 云南 [Yúnnán] restaurant In & Out, and the Chinese for that is 一坐一忘 [Yīzuò Yīwàng]; some photos depicting the 文峰 [Wénfēng] hair salon; and the book he mentioned, The Corpse Walker. There's even a photo of Noah's inspiration Studs Terkel, which includes his name so you can see how on earth it's spelt.

Mosaic of China is me, Oscar Fuchs; editing by Milo de Prieto; artwork by Denny Newell; and China technical support from Alston Gong. See you next week.